Creating a “closed loop” for packaging

The average UK household now recycles 43% of its waste – much more than a few years ago, but still leaving over half of all packaging to end up in landfill. Industry, government and (increasingly) consumers all say they want to see this improve. So why is change proving so hard to achieve? What will it take to “close the loop,” with packaging materials recovered, regenerated and reused instead?

Achieving a “closed loop” requires involvement from many different parties. And the economics need to work for them all, through three important steps:

- The first involves materials and the product suppliers and retailers that use them. A closed loop requires suppliers and retailers to produce packaging that uses previously recycled materials and that can be recycled again after use. That’s not easy to achieve when they are packaging and selling thousands of different products with short and long shelf-lives, every possible size and shape – and when consumers like colourful, good-looking products.

- The second concerns infrastructure and the local authority that arranges it. Collection systems need to be in place to split household and other rubbish, typically a combination of all sorts of materials, into distinct waste streams that can be processed separately. And those systems need to be able to do that cheaply, effectively and consistently.

- The third relates to incentives in the market for recycled materials. In some cases, the value of the reprocessed material will pay for the costs of reprocessing. In others, intervention will be needed to make reprocessing worthwhile and, in turn, to make recycled materials a better choice for future packaging.

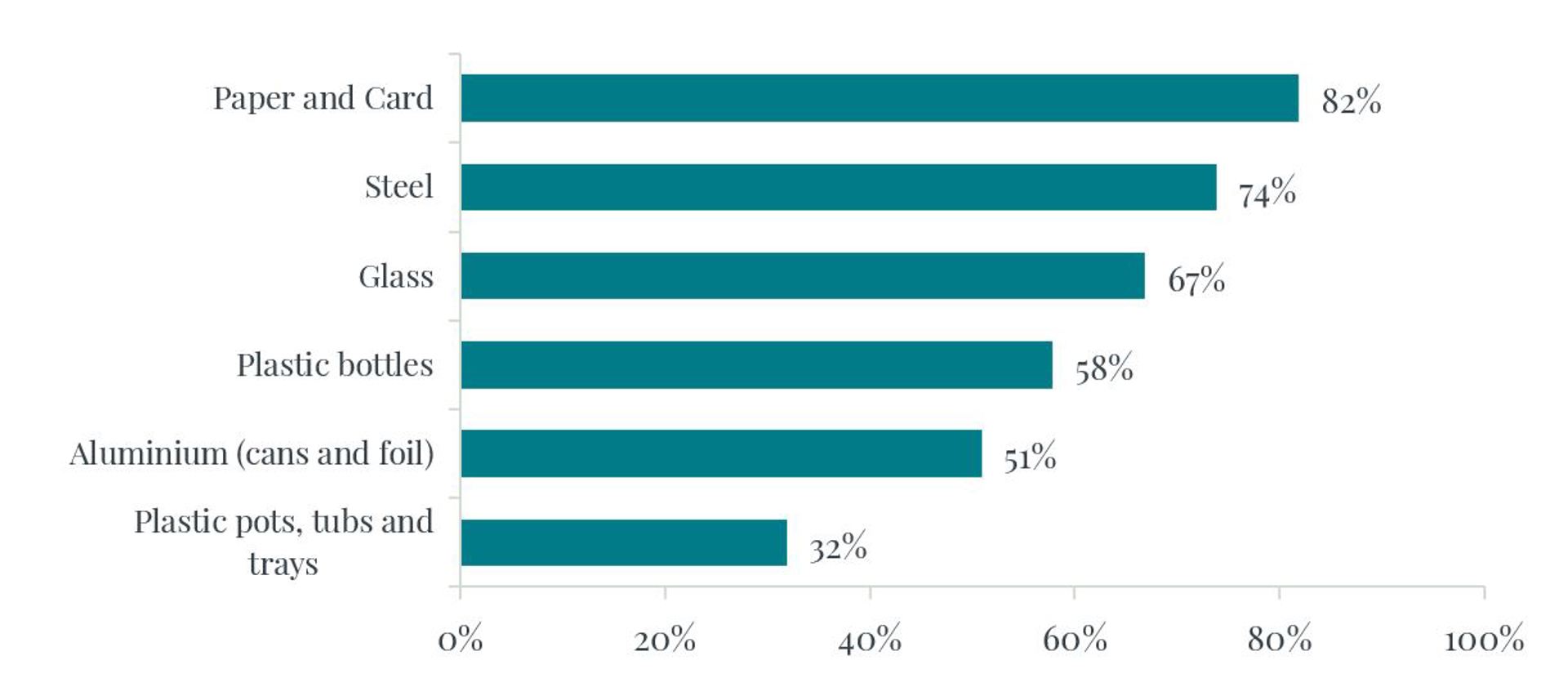

Moreover, there isn’t just one loop. There are several different loops for different materials – each with different economics, overlapping in some places and diverging in others. As Figure 1 shows, we are much nearer to closing the loop for some types of packaging than for others. While some materials, such as plastic pots, still have a long way to go.

Figure 1: Recycling rates by material

Source: DEFRA - UK Statistics on Waste; Recoup, 2018 UK Household Plastics Collection Survey; Plastic statistics from 2017, other data from 2016

Who does what?

With Blue Planet, David Attenborough has helped focus attention on plastic waste, giving a big shove to efforts to get recycling rates up. Some of the most consumer-sensitive (and consumer-visible) creators of such packaging – retailers and the suppliers of branded goods – have been prompted to accelerate their efforts.

Several big suppliers of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) have announced plans to work more with recycled materials, even if over quite long time-scales. Evian, for example, has an ambition to make all its water bottles from 100% recycled materials by 2025. Tesco has gone further, setting itself the target of removing all non-recyclable packaging materials from all its own-brand products by 2019 and hopes in turn to influence the suppliers of other brands that Tesco stocks. Big companies taking such steps can create momentum and create the space and expectation for others to follow.

However, creating products that can be recycled is not much use if the systems are not in place to collect, reprocess and reuse them. A particular challenge is that while many of the creators of packaging (such as Evian or Tesco) work nationally or internationally, the collection infrastructure is often local. In the UK, for example, it is the responsibility of local authorities. But local authorities vary greatly as to when, what and how they collect.

For example, while almost all local authorities collect plastic bottles, one in five will not collect plastic pots, tubs and trays, and four in five will not collect plastic film. This makes it hard for customers to be certain as to what can be recycled, harder to run national campaigns with consistent messages, and harder still to drive a change in habits. And making recycling a matter of habit is an essential aim of policy, since few people want to have to think terribly hard every time they throw something away. Expecting customers to know, remember and respond to the difference in recycling schemes is a big ask.

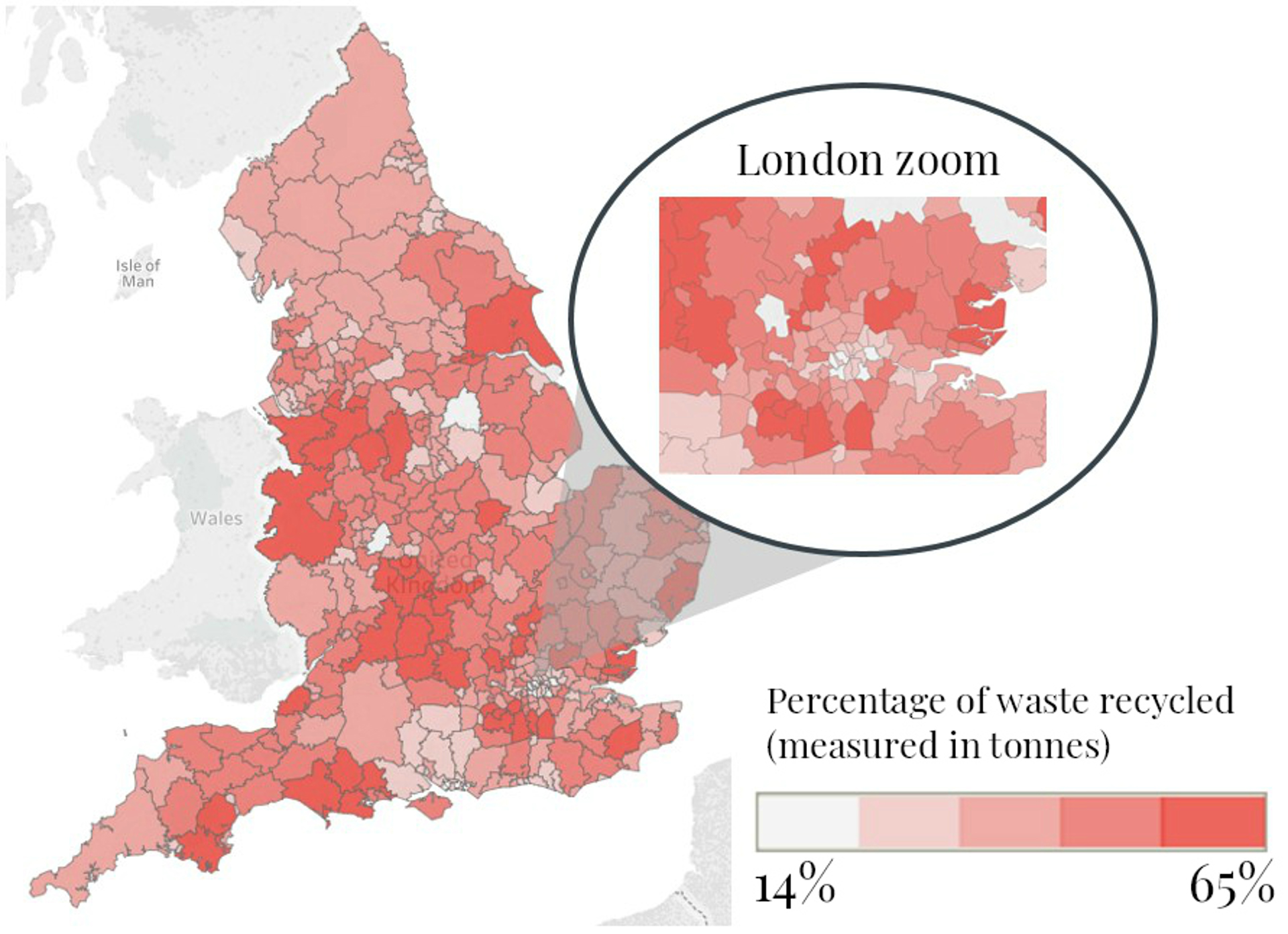

Figure 2: Recycling rates by local authority (2016-17)

Source: www.letsrecycle.com

Note: Some local authorities are grouped together into waste authorities

The alternative, achieving consistency across all local authorities will take both money (in short supply) and greater coordination than exists today. The differing priorities allocated to recycling around the country currently produces significant variation in recycling rates across the country. While 65% of waste material is recycled in the East Riding District of Yorkshire, just 14% is recycled in the London Borough of Newham (see Figure 2).

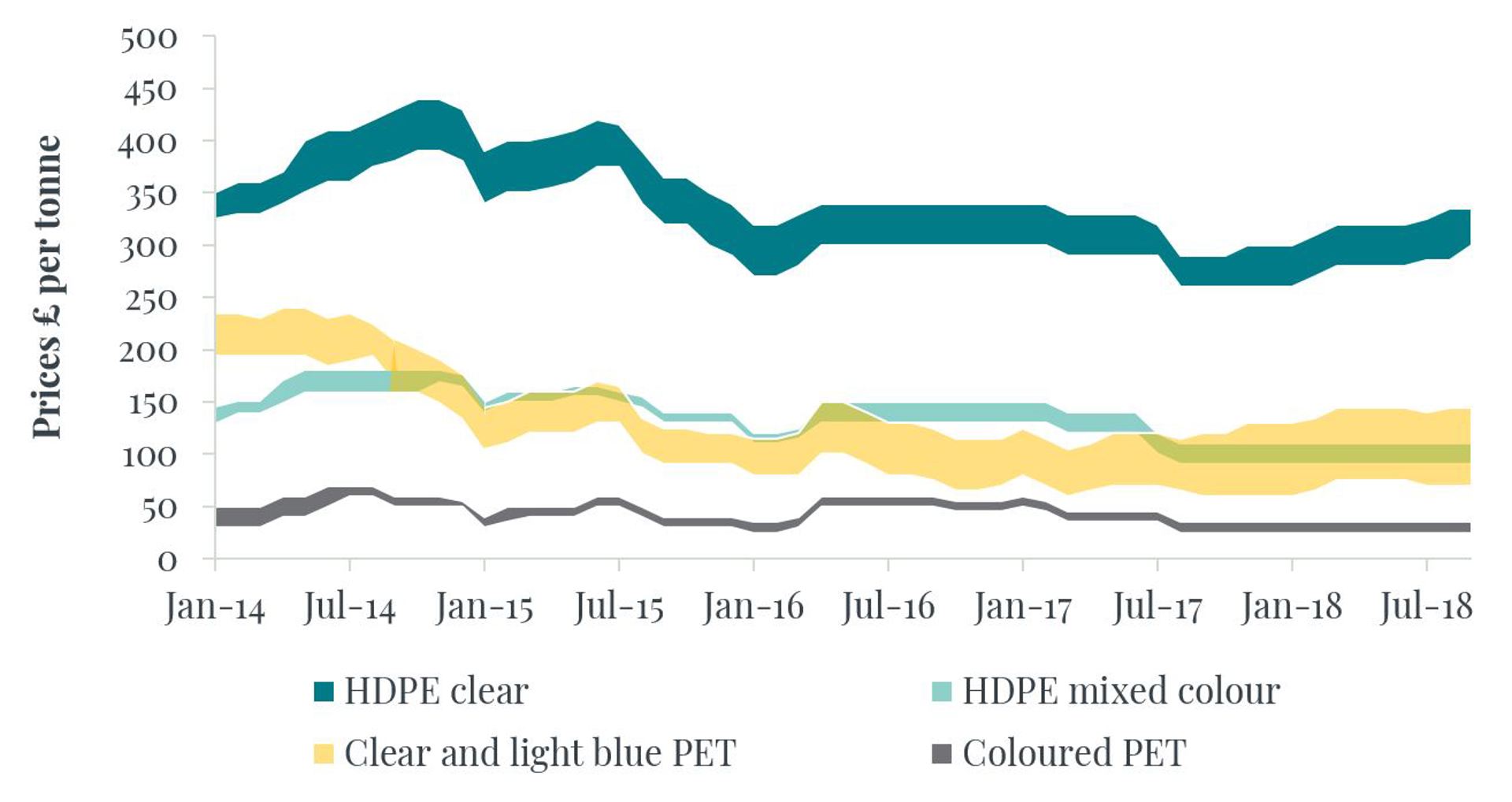

It would undoubtedly help if government acted to create better incentives for all parties, including local authorities. Some waste streams, such as glass, can be self-funding. For many other materials, the restriction on the usage of recycled materials keeps prices low – for example coloured plastic can only be used in the manufacturing of black (or dark) plastics therefore limiting its uses, and as such, it’s worth. In comparison, clear plastic can be transformed into any colour, offering a wide variety of uses following recycling, and therefore having a higher value (see Figure 3). At the same time, reprocessing costs of these materials remain too high to provide a natural economic incentive, and so without both strong consumer pressure and policy intervention, little reprocessing is likely to take place.

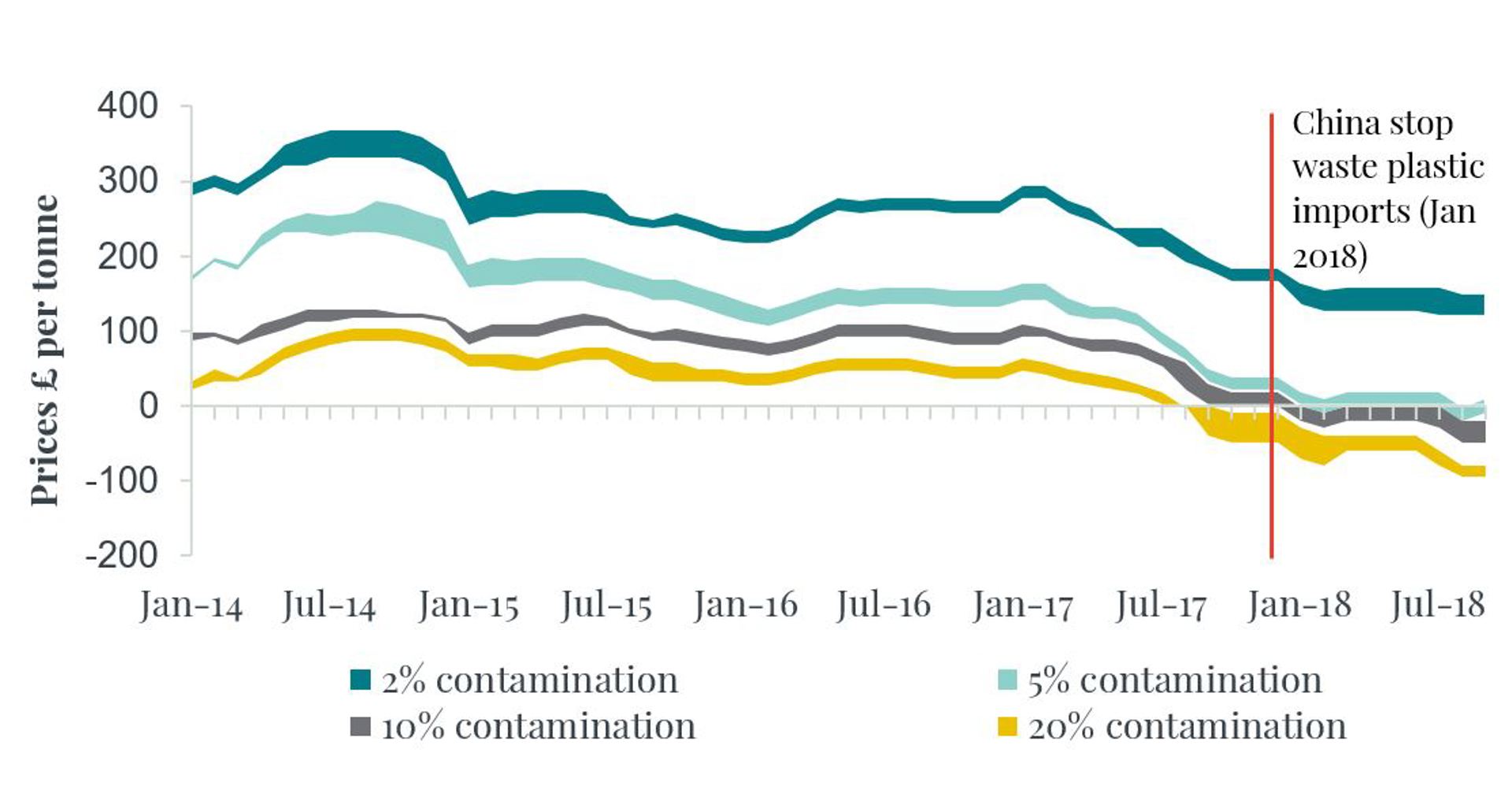

Moreover, China’s increasing reluctance to import European waste has changed the economics by reducing demand and therefore price, particularly for the plastic film that is more contaminated (see Figure 4 for export price of plastics by quality). So unless new reprocessing outlets develop, its likely less collection will happen. Creating new markets for waste is also likely to require help from the policy-makers.

Figure 3: Monthly price range for used plastic bottles by material

Source: www.letsrecycle.com

Figure 4: Monthly price range for plastic film exported by contamination

Source: www.letsrecycle.com and the BBC

All together, now

It takes time to change an industry. It takes even longer when several related industries need to change at the same time, as well as several different arms of government. It will be all too easy for challenges in one area – local authority funding, say – to hold back progress elsewhere. And in turn local authorities will want to be sure that the enthusiasm that some parts of industry are showing at present will be retained – even as David Attenborough’s images of sea life choking on plastic waste fade from people’s minds.

It will take further commitment from industry, backed by smart and targeted regulation, and proactive responses from local authorities, to turn the focus and enthusiasm of the last year turn into lasting change. It is hoped, and expected, that the government’s response – its resources and waste strategy expected before the end of 2018 – will help maintain the momentum that so far has been building from several announcements from industry.