History shows the practical benefits of ground-breaking technologies take time to show up.

The rapid adoption of new digital technology is changing everyday life. But digitisation does not seem to have boosted productivity, the elixir of economic growth. This does not necessarily make it less relevant than the headlines make out. History shows the practical benefits of ground-breaking technologies take time to show up. But it does underline the need for high-speed broadband networks and supporting investments, notably in human capital, if companies are to make the most of artificial intelligence and other innovations. And a firm grasp of the driving forces of productivity and the adoption of new technologies at the firm level will be critical to the formulation of effective public policies to realise the potential of the digital economy.

The digital economy and the “productivity paradox”

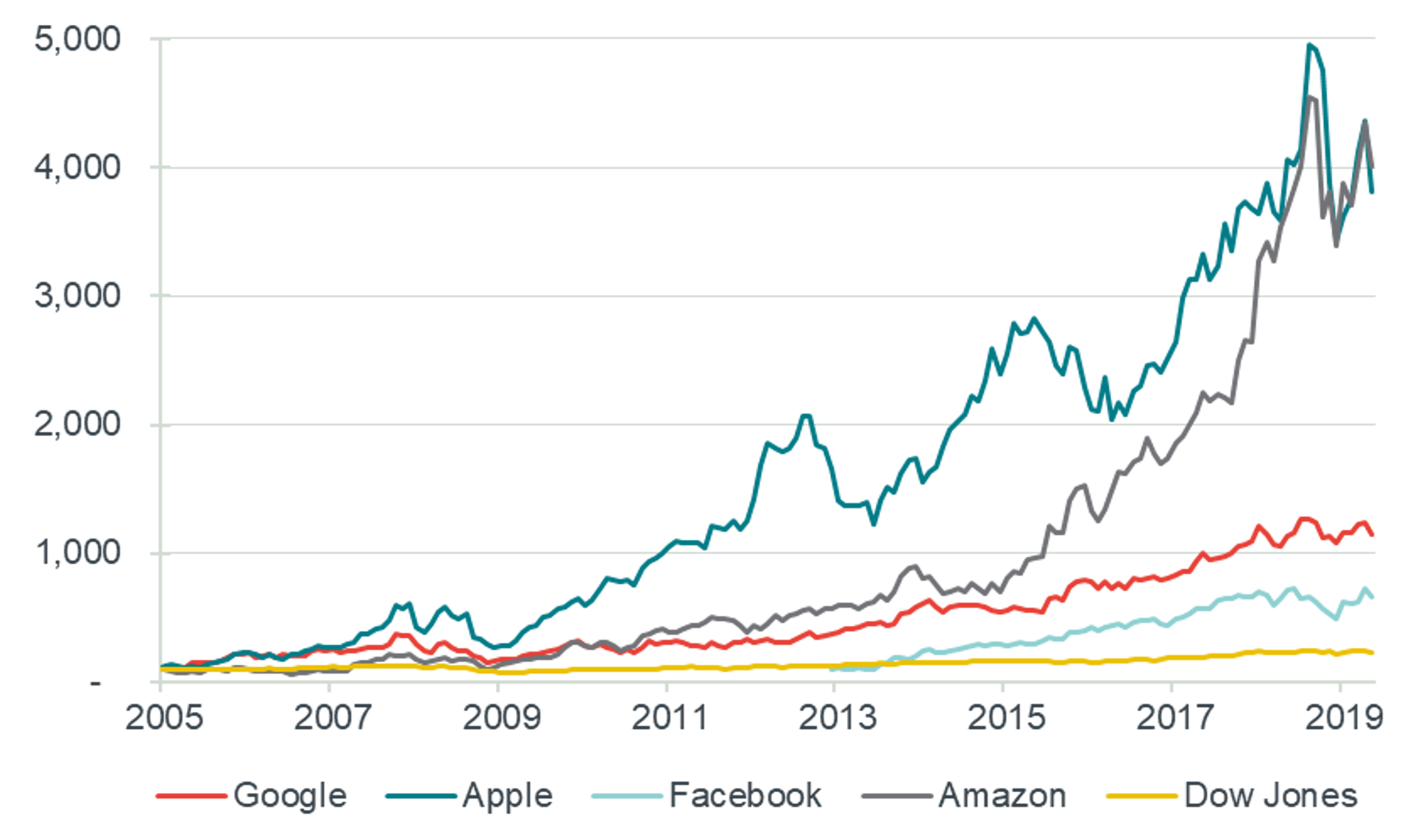

We live in a digital world. Many of our transactions, purchases and interactions with other people are conducted through the Internet and devices connected to telecommunications networks. This has given birth to what is called the “new economy” or the “digital economy”. The size of the digital economy is difficult to measure, but some estimate it at around 10% of a country’s income, value- added and employment. Many of us cannot go anywhere without carrying our smartphone. So it is not surprising that the share prices of the largest Internet firms (also called GAFAs) have significantly outperformed the Dow Jones industrial average. These firms are now amongst the largest in the world.

Figure 1: Indexed stock prices for GAFAs vs Dow Jones

Source: Frontier Economics based on data from Yahoo Finance. All stock prices indexed to 100 in 1/12/2004 except for Facebook (100 in 1/05/2015) as the company was floated in May 2012

The development of this new economy is underpinned, among other things, by the rollout of broadband. In 2004 there were 40m broadband connections in Europe. By 2018, this figure had risen to 177m. Likewise, the share of fixed broadband subscriptions in Europe with a speed of 100 Mbps or above went from 1.6% of the total in 2011 to 25% in 2018.

As the economy becomes more digital, you would expect it to become more productive as well. Online platforms allow retail transactions to take place more easily. Communications between companies are more efficient and cheaper. New services and applications are developed. People have access to an almost unlimited amount of information at the touch of a keypad. Jobseekers are better able to find jobs that match their skills. It is increasingly possible to work remotely. All of this should lead to gains in productivity. And productivity is key to economic growth. However, this does not seem to be the case in practice. The following table shows productivity growth, as measured by Total Factor Productivity (TFP), for 12 of the most developed EU countries between 2002 and 2015, broken down into three time periods. While digitisation of the economy is not the only engine of TFP growth, it’s reasonable to assume that it has important effects. After all, digitisation is one of the main innovations of the past two decades.

Figure 2: Total factor productivity growth

Source: Bart van Ark & Kirsten Jäger, 2017. "Recent Trends in Europe's Output and Productivity Growth Performance at the Sector Level, 2002-2015," International Productivity Monitor, Centre for the Study of Living Standards, vol. 33, pages 8-23, Fall.

As the table shows, TFP grew in only two of the three periods and only very modestly (0.5% and 0.2%). In 2008-2010, at the time of the financial crisis, TFP actually fell 1%. This is not the only evidence of the apparent disconnect between productivity and the digital world. The following figure seems to confirm that there is no apparent relationship between broadband penetration in enterprises and TFP growth.

Figure 3: Relationship between TFP and enterprise fixed broadband penetration

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators. Note: The size of the bubbles represents the percentage of enterprises with fixed fast broadband (above 30Mbps)

So the digital world is changing habits but not productivity?

There is no doubt that technology is transforming people’s everyday lives. However, at a more aggregated level, we seem to be witnessing a new version of Solow’s productivity paradox in the computer age. It may be true that sometimes we are overly optimistic about the effect of new technologies on the economy. However, what may well be happening is that the main impact of technological innovations (e.g. artificial intelligence, internet of things, big data) is still to be felt. In other words: “It takes a considerable time, more than is commonly appreciated, to sufficiently harness new technologies.” This was notably the case with electricity. The first electric motors were introduced in the early 1880s, but it took 40 years for US manufacturing productivity to soar.

Understanding why this is the case will be critical to the decisions that policymakers need to make over the coming years to continue promoting the digital economy. In our view, there are indications that we need more investment in digital infrastructure, not less, and a greater public policy emphasis on digitisation. Some basic figures at the company level underpin this argument.

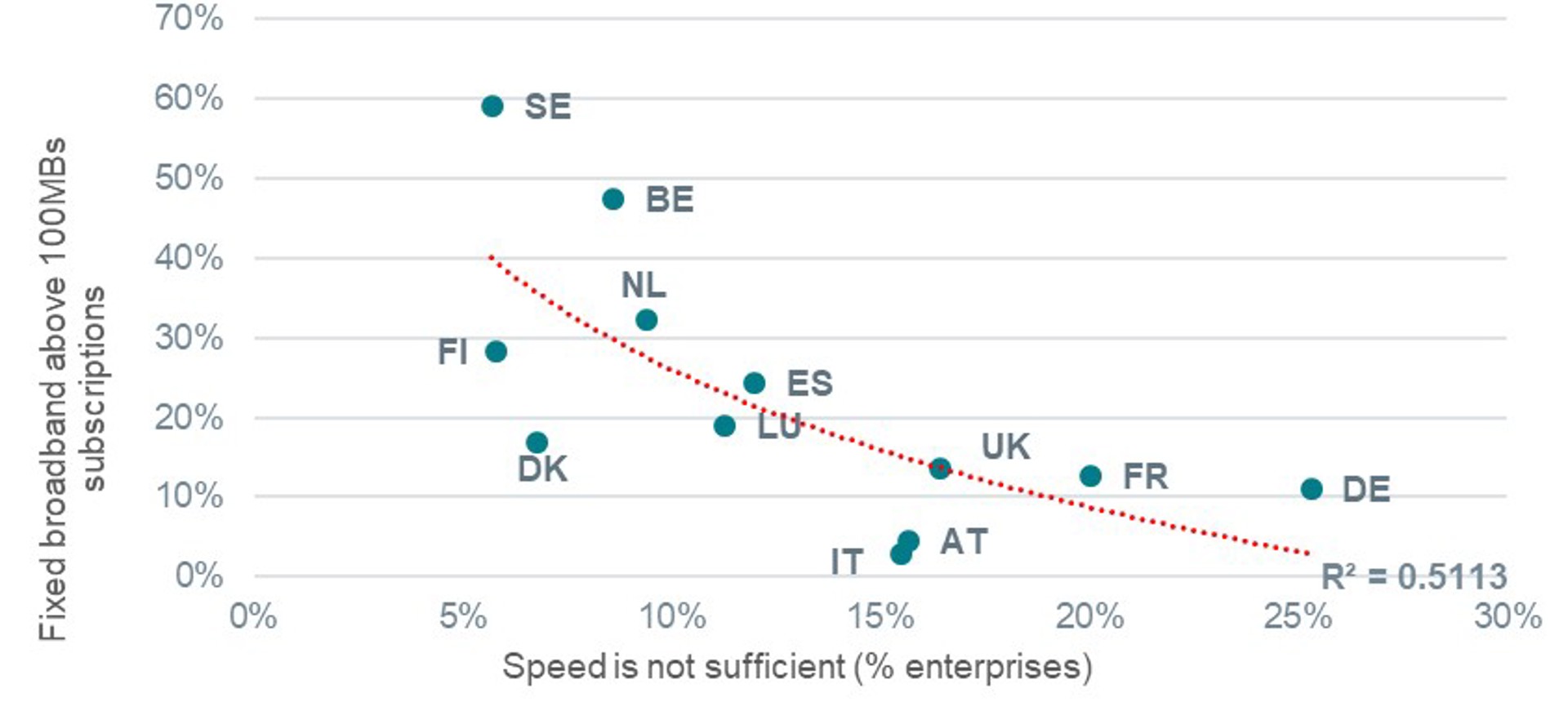

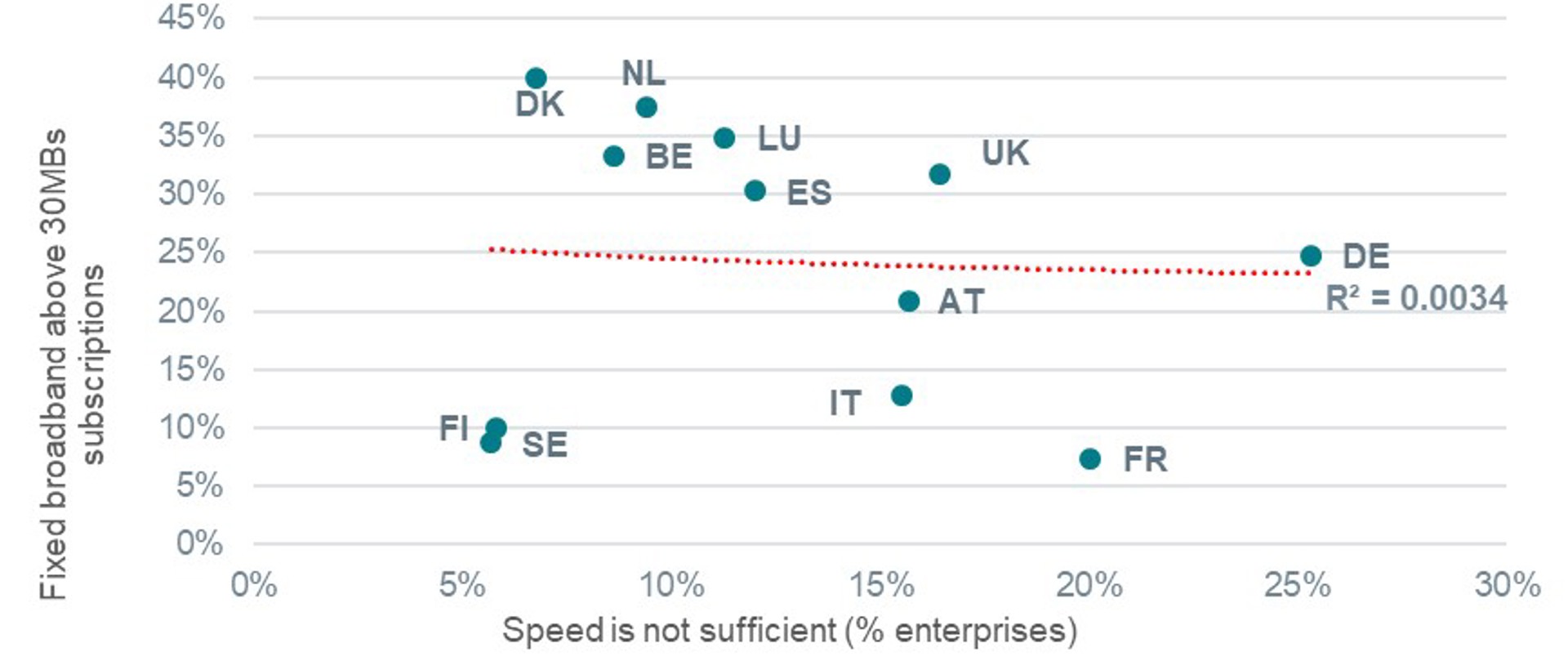

Companies are crying out for faster broadband. According to EU surveys, enterprises say they need ultra-fast broadband (UFBB, with speeds above 100Mbps) to do their business. Figures 4 and 5 analyse the relation between companies’ complaints about insufficient speed and several speeds. Apparently there is a clearer relationship between faster speeds (100MBs) the speed needed by the undertakes. In particular, the enterprises that do not have 100Mbs subscriptions are the ones that requires that more speed is needed on the EU survey.

Figure 4: Relationship between firms’ need about speed and broadband speed (100MBs)

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators

Figure 5: Relationship between firms’ need about speed and broadband speed (>30MBs)

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators

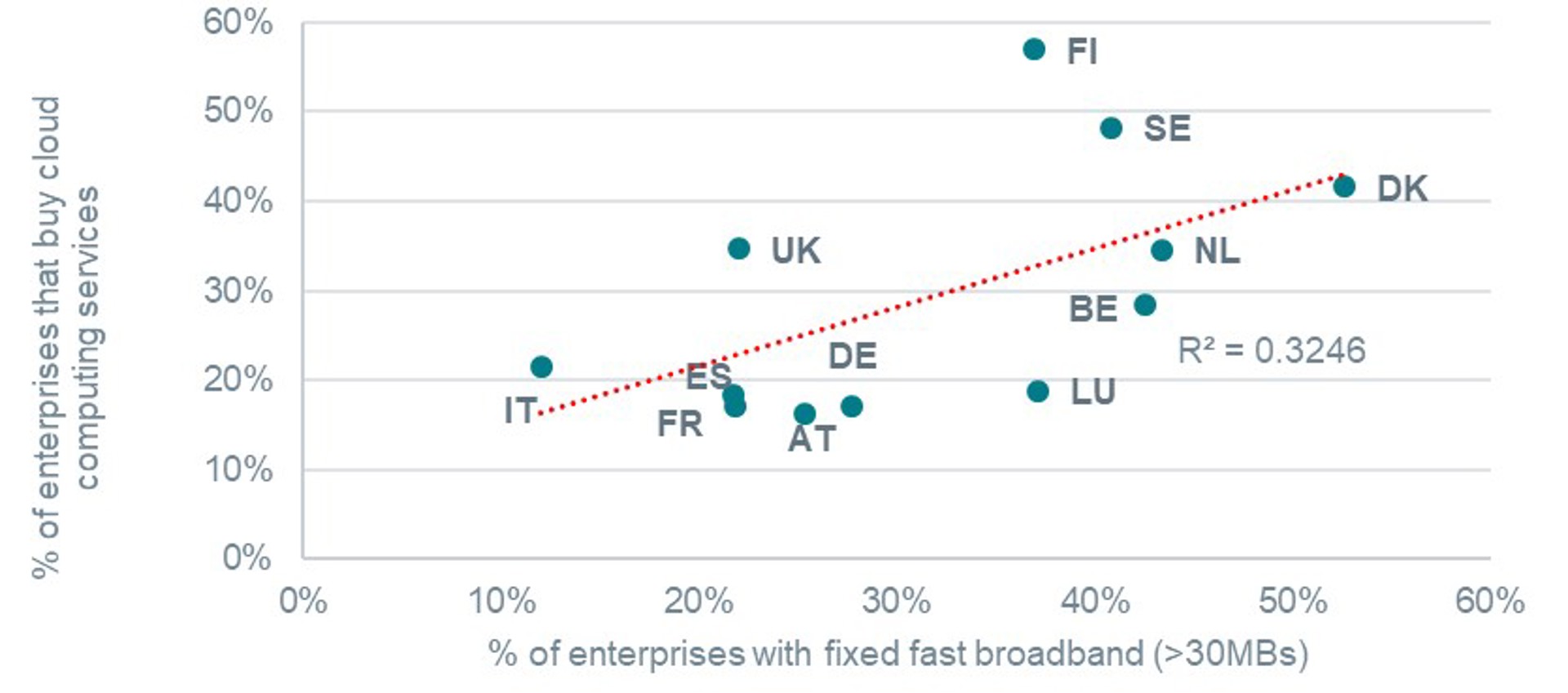

Broadband networks are only as useful as the services that are delivered over them. For example, data at European level indicates that the use of cloud services by enterprises is relatively low. The modest take-up seems to be positively correlated with the penetration of fast broadband subscriptions.

Figure 6: Relationship between high digital services and fast broadband subscriptions

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators

Better telecommunications networks may not be enough

Access to UFBB may not be enough to reap the benefits of the new age of technology, and other complementary investments will need to be made. For instance Fabling et al (2016) show that firms need to make additional, complementary investments in organisational capital and strategy management if UFBB is to be the springboard for productivity growth.

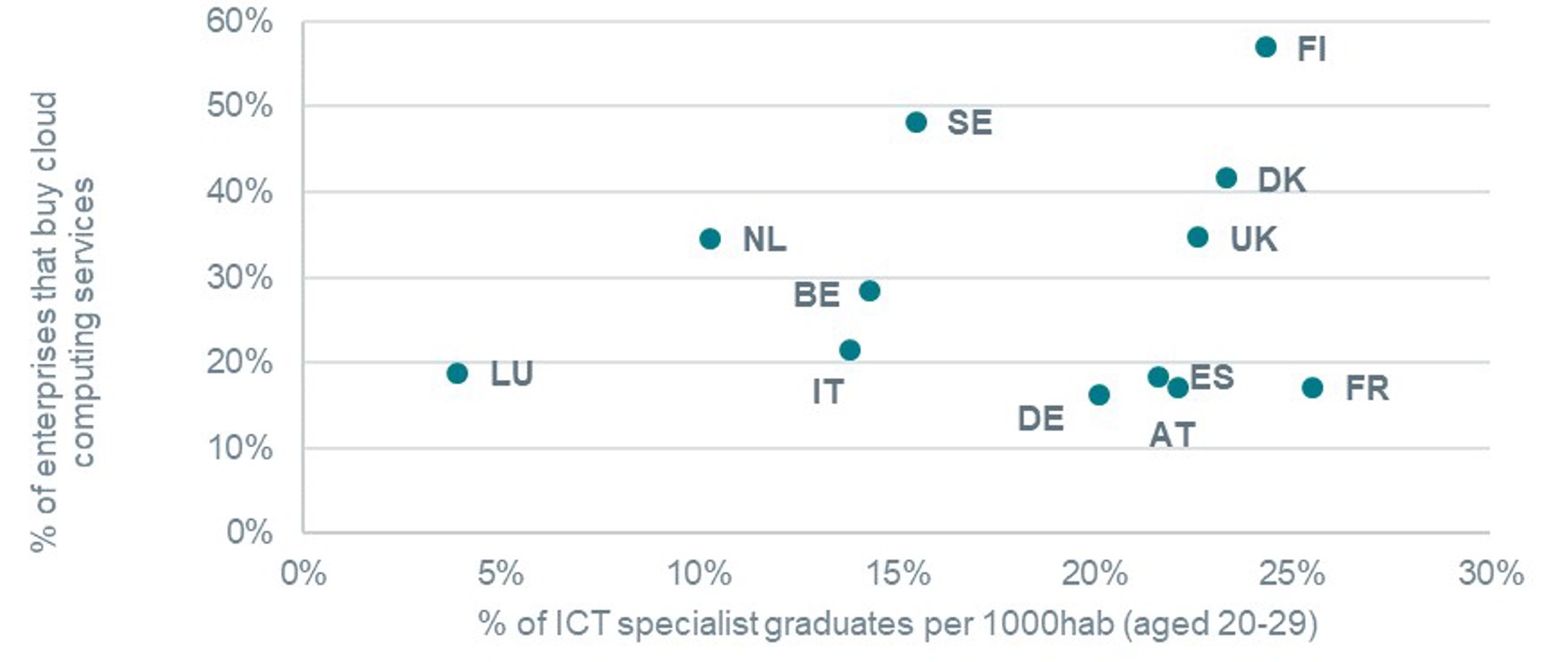

In the figure below we see that EU countries where enterprises make more use of cloud services also have more ICT specialists, which could indicate that more investment in human capital will be necessary.

Figure 7: Relationship between new cloud services and ICT specialists

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators

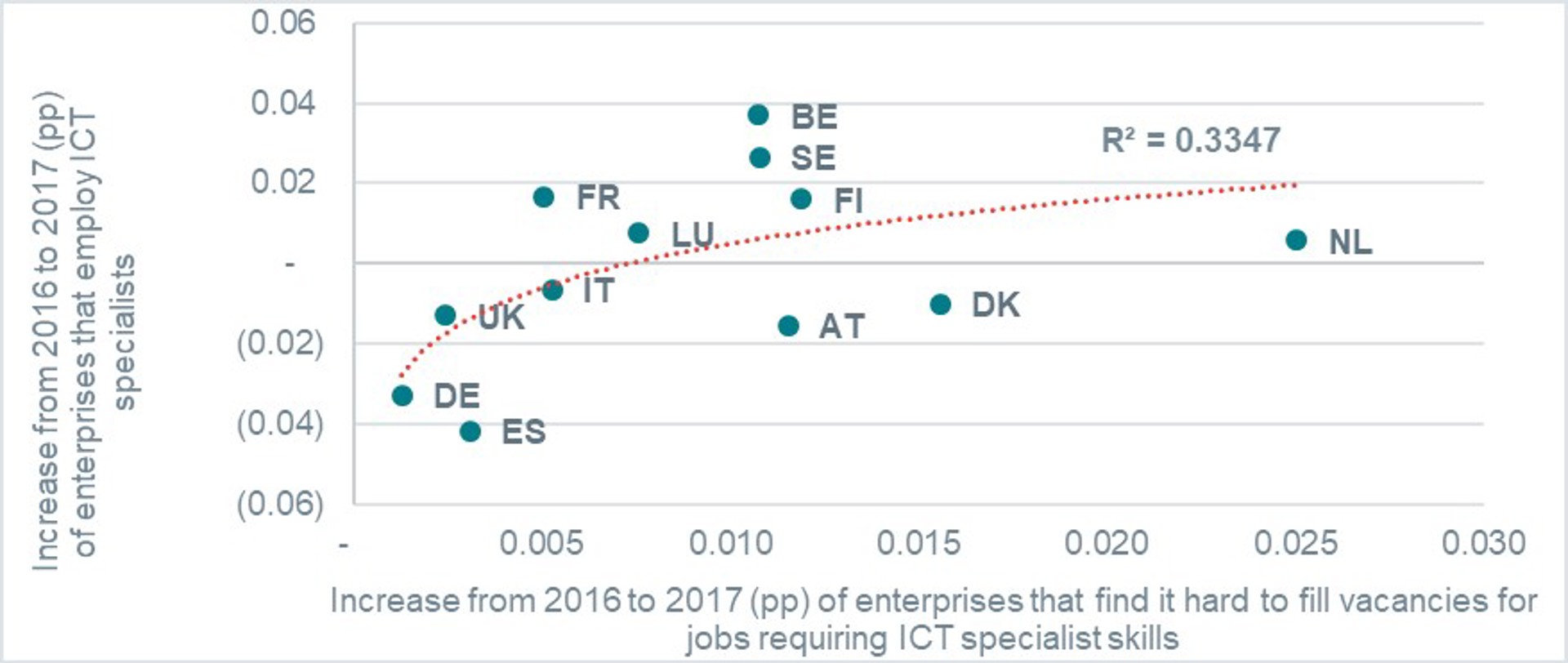

In fact, there may be a shortage of ICT experts in the EU, as the rate of ICT recruitment does not seem to reduce the difficulties firms face in hiring ICT experts.

Figure 8: Increase of enterprises that employ ICT specialists with respect to the increase of the difficulty to fill vacancies requiring ICT specialists

Source: Frontier Economics analysis based on EC: Digital Agenda Scorecard Indicators

Therefore, more investment in human capital, among other things, will be crucial for the economy to take full advantage of technological innovations. Specifically, future economic progress will depend in part on understanding exactly what ICT skills are required.

Conclusion

The promise that a golden age of new technology and high-speed telecommunications would transform the economy has not yet come true. At least it does not seem to be reflected in the standard macroeconomic statistics, notably for productivity.

There are several explanations for this paradox. Perhaps our expectations of these technologies are too high? Or perhaps their full potential has yet to be realised? We lean towards the second proposition. Basic statistics show that enterprises, which is where productivity increases will show up first, need ultra-fast broadband networks and supporting investments to harness the benefits of the new technologies. Investment in human capital, notably ICT specialists, is particularly important. For governments, understanding what is behind productivity growth and the adoption of new technologies at the firm level holds the key to the design of sound public policies.