Discussion of election pledges to extend free childcare places for preschool children in England has focused on the cost to government with relatively little attention given to the scale of change required to deliver the increases in the number of government funded hours.

Working in collaboration with London South Bank University Honorary Research Fellow, Pamela Calder, Frontier has estimated that substantial expansions in early years childcare provision would be required to fulfil these campaign promises or to deliver a universal system of free “cradle to school” full-time childcare. We also asked how the proposals to raise provision quality and increase funding rates may improve child outcomes.

What’s on offer?

All three and four year old preschool children are currently entitled to 15 hours of free early education for 38 weeks each year and an additional 15 hours per week if their parents are working. Two year old children living in more disadvantaged families (roughly the bottom 40 percent in the income distribution) are also entitled to 15 hours each week for 38 weeks each year.

The manifestos of two parties include pledges to expand this provision of free hours for preschool children:

- The Labour Party proposes to extend the offer of 30 hours for 38 weeks to all preschool children aged two to four, regardless of parental work or income level.

- The Liberal Democrats propose to extend the offer to 35 hours each week for 48 weeks each year to all preschool children aged two to four (again, regardless of parental work or income level) and to children aged between 9 months and two years if their parents are working.

Under both proposals, the number of free hours offered would be increased for already eligible children (particularly for three and four year olds with non-working parents and two year olds in disadvantaged families), while two year olds in the least disadvantaged families would be offered free hours for the first time. The Liberal Democrats would also offer free hours to children of working parents aged under two for the first time.

We also consider an even broader offer of universal free “cradle to school” full time childcare which would extend the Liberal Democrat offer to all children aged six months or older:

- A “cradle to school” offer of 35 hours each week for 48 weeks each year for all children from 6 months to school start (defined as the September after they turn four).

How much more childcare would be needed?

Measuring whether any expansion in early years provision would be required to deliver these additional free hours might seem a relatively straightforward exercise, achieved by simply comparing

the total number of hours currently delivered (both government funded and paid by parents) with the numbers of children in the relevant age groups and the number of funded hours that would be used by each child. However, we had to address a number of issues to make this comparison:

- There are no publicly available statistics on current preschool provision by child age and separately for term time and school holiday periods. To address this, we analysed data from the Survey of Childcare and Early Years Providers (SCEYP) to estimate the total number of hours of provision currently delivered to preschool children of different ages in England during term-time and during the school holidays.

- Children currently become eligible for free hours at the start of the term following their third (or second) birthday and effectively cease to be eligible for free preschool hours when they enter school reception classes in the September following their fourth birthday. To consider the point of peak demand in the summer term (just before an entire year cease to be eligible), we use annual rates of live births for England to estimate the number of children in each preschool age group as of 1st April 2020.

- We use current estimates of take-up of the universal 15 hours offer and use of the additional 15 hours by working parents to estimate the proportion of children in the eligible age groups who would use the hours.

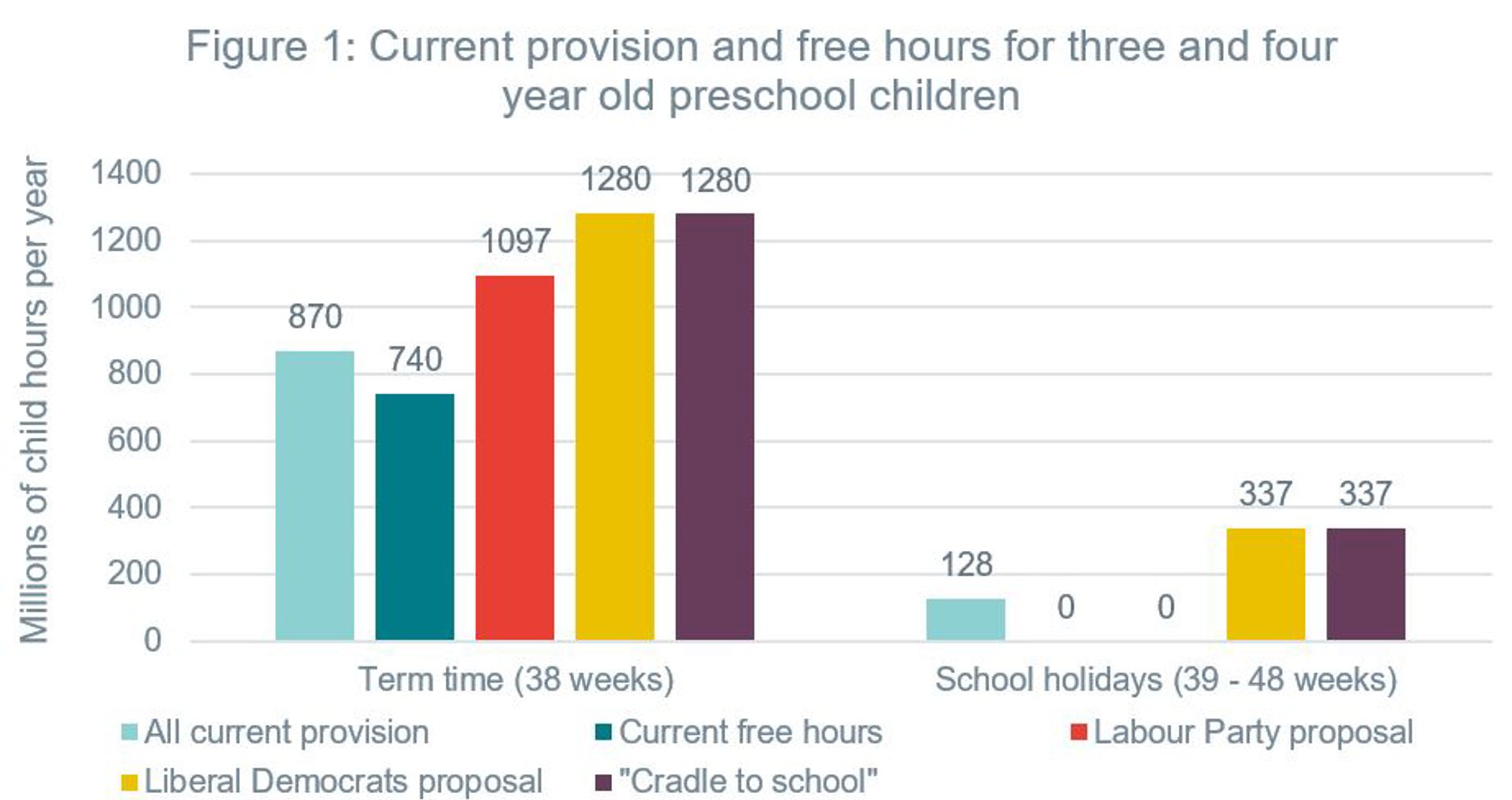

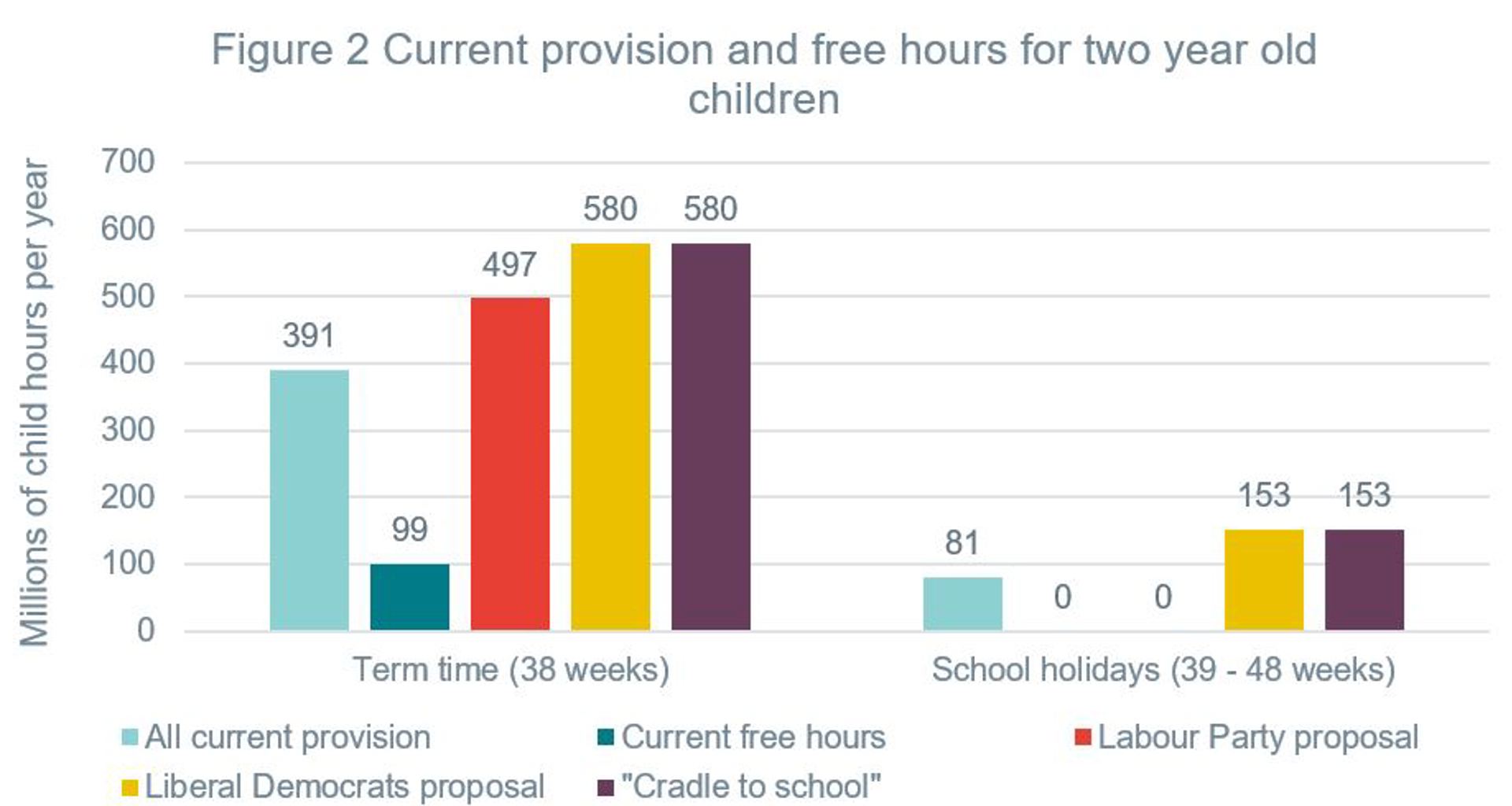

Figures 1 to 3 present the comparisons of all current provision (free hours and parent-paid hours) during term time and during school holidays with the number of free hours estimated to be required under the current system and the alternative proposals. For simplicity, it has been assumed that the free hours for 38 weeks under the current and proposed policies are all taken during the term, although they can be (and sometimes are) spread across the entire year.

It is important to note that these estimated increases in provision are lower bounds because they assume that all available provision would be used for free hours. The required expansion would be greater to the extent that parents would wish to pay for hours in addition to the free hours.

The numbers for term time in figures 1 and 2 show that the estimated provision required for the currently offered free hours falls comfortably within actual provision (740 of the 870 million hours for three and four year olds and 99 of the 391 million hours for two year olds). For these two age groups, the Labour Party proposals would require an estimated expansion of around 30 percent in the number of hours during term (1097 million hours compared to 870 million hours for three and four year olds, and 497 million hours compared to 391 million hours for two year olds). The Labour Party proposes to increase the number of early years staff by 150,000, an increase of 42 percent (from 363,400 in summer 2019) which (if average hours per staff were constant), would provide adequate additional staffing to cover a 30 percent expansion in provision. The Liberal Democrats’ proposal (and the “cradle to school” option which is identical for these age groups) would require increases in provision of around 50 percent for both age groups, reflecting the higher weekly number of free hours.

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the SCEYP, 2018

Figures 1 and 2 show that current provision during school holidays is lower than during term, even allowing for the fact that the holidays only cover one quarter the number of weeks than those covered by term time. This is because many providers are only open during term, particularly school based providers with nursery provision only for three and four year olds. Consequently, the Liberal Democrats proposals for 48 weeks of childcare for all two to four year olds (and the identical “cradle to school” for these age groups) would require even greater expansion of provision during the holidays: the estimates suggest provision would need to be more than two-and-a-half times its current size for three and four year olds and almost twice its current size for two year olds.

Figure 3 shows how expanding provision to children of working parents under age two (the Liberal Democrats’ proposal) would require expansions of around 20 percent during term and 30 percent during the holidays. Given that much of the current provision for this age group is used by working parents, this expansion reflects an implicit assumption in our calculations that work participation would be slightly higher as a result of the free hours. The extremely large expansions under the “cradle to school” option for this age group mainly reflects the offer for all children regardless of parent work (and the additional 3 months of free hours to a lesser extent). What this shows is that providing anything like a “cradle to school” full-time childcare offer for all families would require a particularly dramatic expansion in childcare for children under age two.

What kind of additional provision would benefit children?

The numbers presented above provide insights into the quantity of provision required to offer parents free hours to support them to work, but the quality of the additional free hours needs to be considered to understand the possible impacts on children. A wide range of evidence has shown that high quality provision is critical to support children’s cognitive and social development and this is associated with the use of more highly qualified (and consequently higher paid) staff. Both the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats emphasise that the free hours will be high quality and propose a transition to a graduate-led workforce (meaning that every setting would have at least one member of staff qualified to graduate level).

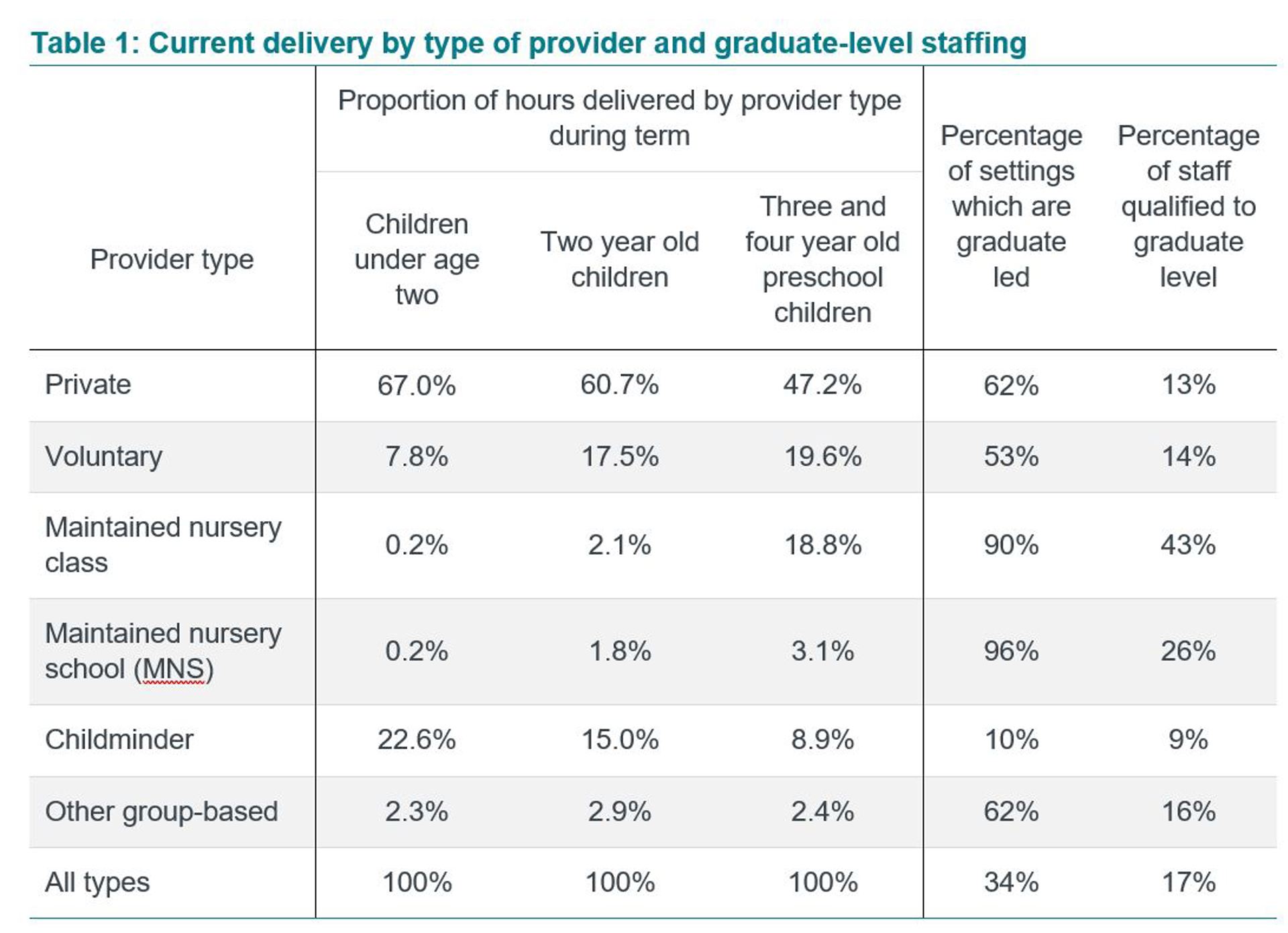

At present, 17 percent of the early years workforce are qualified to graduate level and we estimate that around one third (34 percent) of settings are graduate-led. Any transition to an entirely graduate-led early years sector would require either considerable additional training to graduate level or a redistribution of graduate-level staff across settings.

As shown in table 1, the proportion of settings which are graduate-led and the proportion of staff qualified to graduate level are considerably higher for maintained provision (maintained nursery classes and maintained nursery schools) than other types of providers. Maintained providers also score more highly, on average, than private and voluntary providers on more direct measures of quality. However table 1 also shows that only 4 percent of hours for two year olds and 22 percent of hours for three and four year old preschool children are provided by the maintained sector. Moreover, the experience following the introduction of free hours for three year olds in 2004 suggests that much of any expansion in provision would be delivered by private and voluntary providers. Hence, raising quality would either require some means to increase the share of graduate-led settings within the private and voluntary sector or supporting expansion in provision in the maintained sector, particularly for children aged two and younger. Such expansion in the maintained sector would increase the opportunities for children to remain with a single, highly qualified provider throughout their preschool years and through into school.

Both the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats have proposed substantial increases in the hourly funding rates for the free hours which could help cover the higher costs of a more highly qualified workforce. More broadly, while higher funding per se offers providers the opportunity to improve quality (and many may take that opportunity), there is no guarantee that providers will use the money to achieve this. Some might choose alternative uses such as increasing staff pay or giving parents more flexibility, while others could simply pocket the extra funding as additional profit. Hence, it is important that increases in funding intended to improve quality are introduced alongside additional quality-related requirements.

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from the SCEYP, 2018

Conclusions

The election campaign has been instrumental in raising some key issues in early childhood education and care: the Labour Party have highlighted the importance of quality of provision as well as quantity; the Liberal Democrats have raised the issue of bridging the gap in support for really young children; and the Conservatives have discussed wrap-around care for school children. While the budget costs of the campaign promises may be of considerable concern, it is perhaps more important to understand the scale of changes that the proposals would aim to achieve, both in the quantity and in the quality of early years provision.