This weekend marked the opening of the 2020-21 Premier League season. Top division football’s return to action in England has been accompanied by intense scrutiny of the finances of the world’s most-watched football league. Amidst the economic fallout from the Coronavirus pandemic, Premier League footballers have faced mounting calls to accept pay cuts, and a small number of clubs have succeeded in negotiating temporary wage cuts with players. But there is little evidence to suggest that a more permanent levelling-down of player pay is imminent. Instead, the league – and its players – look set to thrive financially in a post-pandemic recovery.

Some find the take-home pay of Premier League stars simply beggars belief. Manchester United goalkeeper David De Gea, the league’s highest paid player, earns a weekly wage of £375,000. The median weekly wage for full-time employees in the UK was £585 in April 2019: so it would take the “average” worker over 12 years and 3 months to match De Gea’s earnings in a single week. But as economists say, it’s all about market forces: a limited supply of the greatest skills, and soaring demand for them.

It’s the economics, obviously

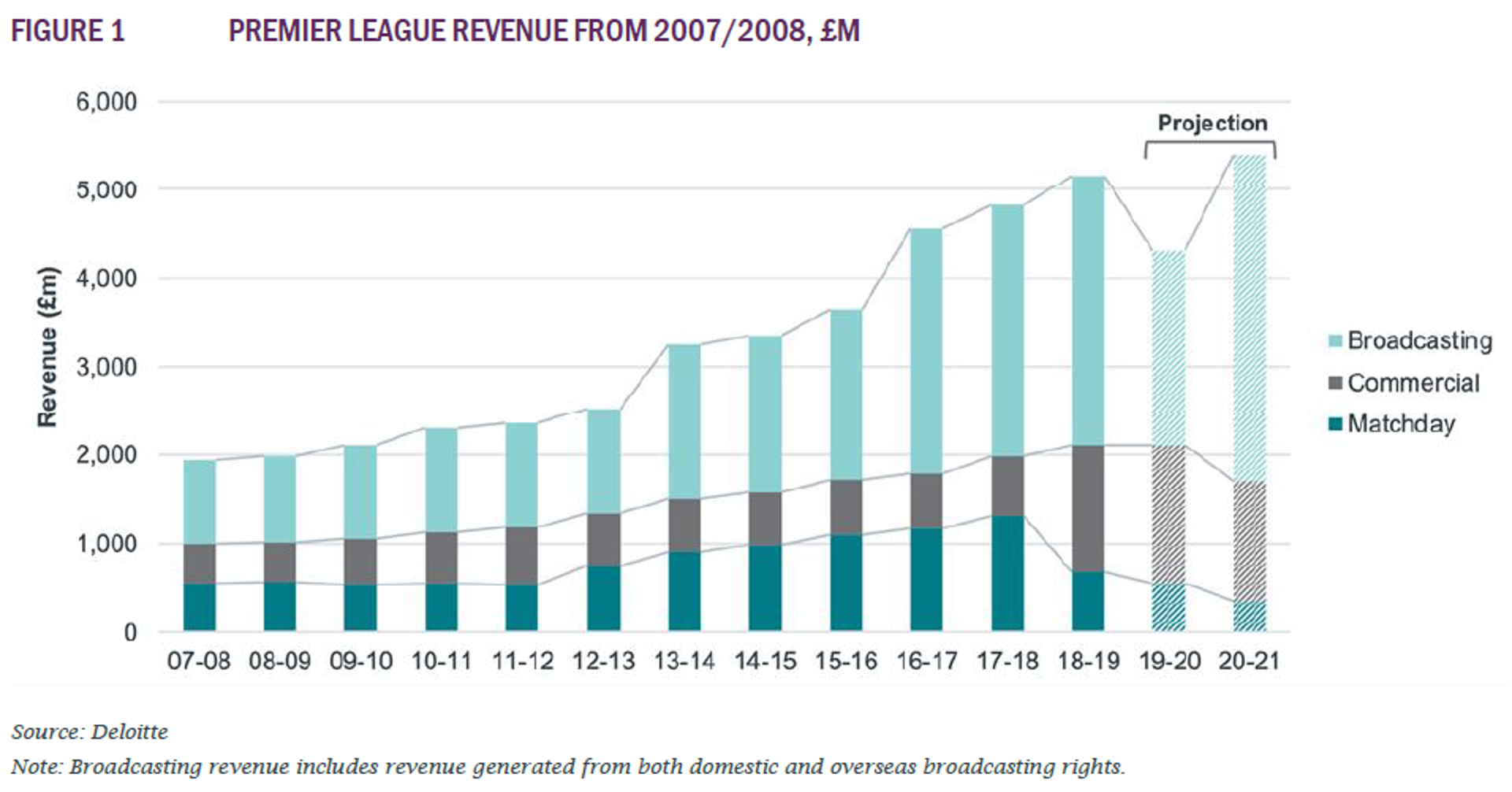

Since the Premier League was launched in 1992, revenue earnings of the clubs in the league have grown almost exponentially, driven by its growing commercial appeal and the succession of increasingly lucrative rights deals signed with television broadcasters. Since 2007, the clubs’ revenues have grown almost 180% (see Figure 1). About 50% of broadcasting revenues are allocated between the clubs on the basis of performance, as well as how often a club’s matches are broadcast live in the UK. In pursuit of success and exposure, clubs have had a clear incentive to compete for – and subsequently reward – the very best players.

The pool of quality candidates, though, is limited. Out of 1.5m children playing organised youth football in England today, only 180 – or 0.012% – will make it as a Premier League professional. As in any labour market, skill shortages increase the wages of the skilled. Premier League wages have increased by 2,811% since 1992, compared with a general rise in inflation over the same period of only 109%. The 2018-19 season also saw the league’s collective wage bill break the £3 billion threshold for the first time in history.

In the second quarter (March to June) of 2020, growth in workers’ nominal earnings in the UK turned negative for the first time on record. The figures were dragged down mainly by pay cuts for younger, low-paid workers. So the Premier League stars – amongst the economy’s highest earners – have been “encouraged” to accept significant wage cuts too. Politically and even morally, that makes sense; business-wise, perhaps less so.

A game of two halves

The Premier League has not, of course, been immune from Covid-19’s economic impact. Losses of at least £500m have been estimated for the 2019-20 season. Matchday revenue plummeted following the ban on fan attendance at matches since February, and with the Government planning to allow only a partial reopening of stadiums from October (at the earliest), matchday revenue for the coming season is projected to be at least £300m below 2018-19 levels. Meanwhile rebates had to be issued to broadcasters following the league’s three-month, mid-season, suspension in March.

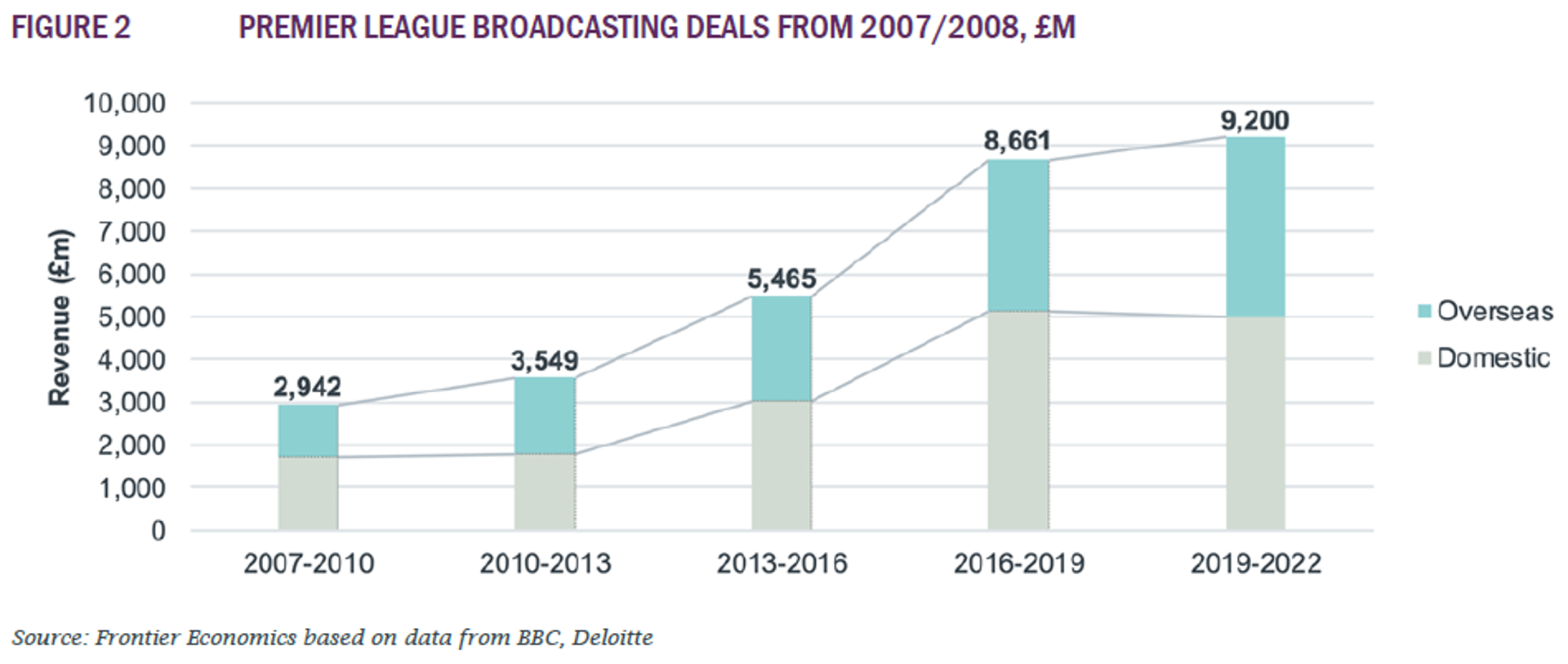

Even so, the league looks set for a record season in 2020-21. Revenue is projected at £5.4 billion, with clubs set to benefit from the second year of a new, more lucrative broadcasting deal (see Figure 2) that runs until 2022. They are also expected to receive a portion of broadcasting payments deferred from last season. On these figures, there would be no business need for a permanent restructuring of player remuneration.

Of course, matchday revenue will continue to be a weak point while stadiums remain empty, and those clubs with the highest capacity stadiums will suffer most. However, its contribution towards Premier League clubs’ revenues was already declining. Between the 1992-93 and 2018-19 seasons, the share of matchday revenue in overall club revenues fell from 43% to 13%.In contrast, broadcasting revenues accounted for 59% of total revenue in 2018-19, and are expected to rise to 69% in 2020-21.

The increasing importance of at-home fans – and the value broadcasters place on these fans as pay-TV subscribers – provides clubs with something of a safety net. This raises hopes of a ‘V-shaped’ recovery in the league’s finances, strengthened by a tried-and-tested protocol for staging matches during a public health crisis (as demonstrated by the league’s successful return to play last season). The prospect bolsters Premier League players’ resistance to wage cuts.

Such a recovery would seem to be in stark contrast to other sectors of the economy – think retail, hospitality, and services. In these (and other) sectors, the need for continued social distancing has been significantly more damaging and is likely to slow recovery. Nor is football as a whole likely to recover as quickly or successfully as the Premier League. The majority of professional footballers in England ply their trade in the country’s lower divisions, few of which have access to a broadcast revenue safety net, and all of which rely heavily on matchday revenues. These clubs and their players are likely to see incomes hit hard.

The Premier League, however, has a very different economic model. Broadcasting revenues look set to drive its financial recovery; but they will also heighten the competition (and reward) for talent. Covid-19 has demonstrated that elite football can continue without the presence of its fans; but player talent remains both scarce and indispensable.