Recent years have seen an expansion of the role and importance of competition law, with the actions of competition authorities being front page news. And while many aspects of normal life have been put on hold during the pandemic, competition law will continue to make the headlines in 2021.

We have picked out four themes to be aware of this year:

- the impact of Brexit for global mergers;

- the revolution in digital antitrust;

- the impact of the General Court’s Judgment in CK Telecoms; and

- the juggernaut that is the Trucks litigation.

1. Brexit and the CMA

Not for the first time, the impact of the UK’s departure from the European Union is featuring prominently in debates about the outlook for competition policy in Europe. Brexit is now a reality and in 2021 the effect will be felt most keenly in the sphere of merger control. With the end of the transition period, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) will now gain jurisdiction over a range of mergers that would previously have been the exclusive purview of the European Commission (EC). This means that mergers that materially affect consumers in the UK as well as the EU will now be separately investigated by both the CMA and EC. What does this mean for businesses?

At first blush the impact may appear limited. After all, many companies operate in globalised markets that require them to seek clearance in multiple jurisdictions when looking to merge. To take just one current example, the London Stock Exchange Group’s acquisition of data provider Refinitiv – which the EC conditionally cleared this month – had to be cleared by competition authorities in more than a dozen jurisdictions around the world. Will adding one more to the to-do list really make that much difference?

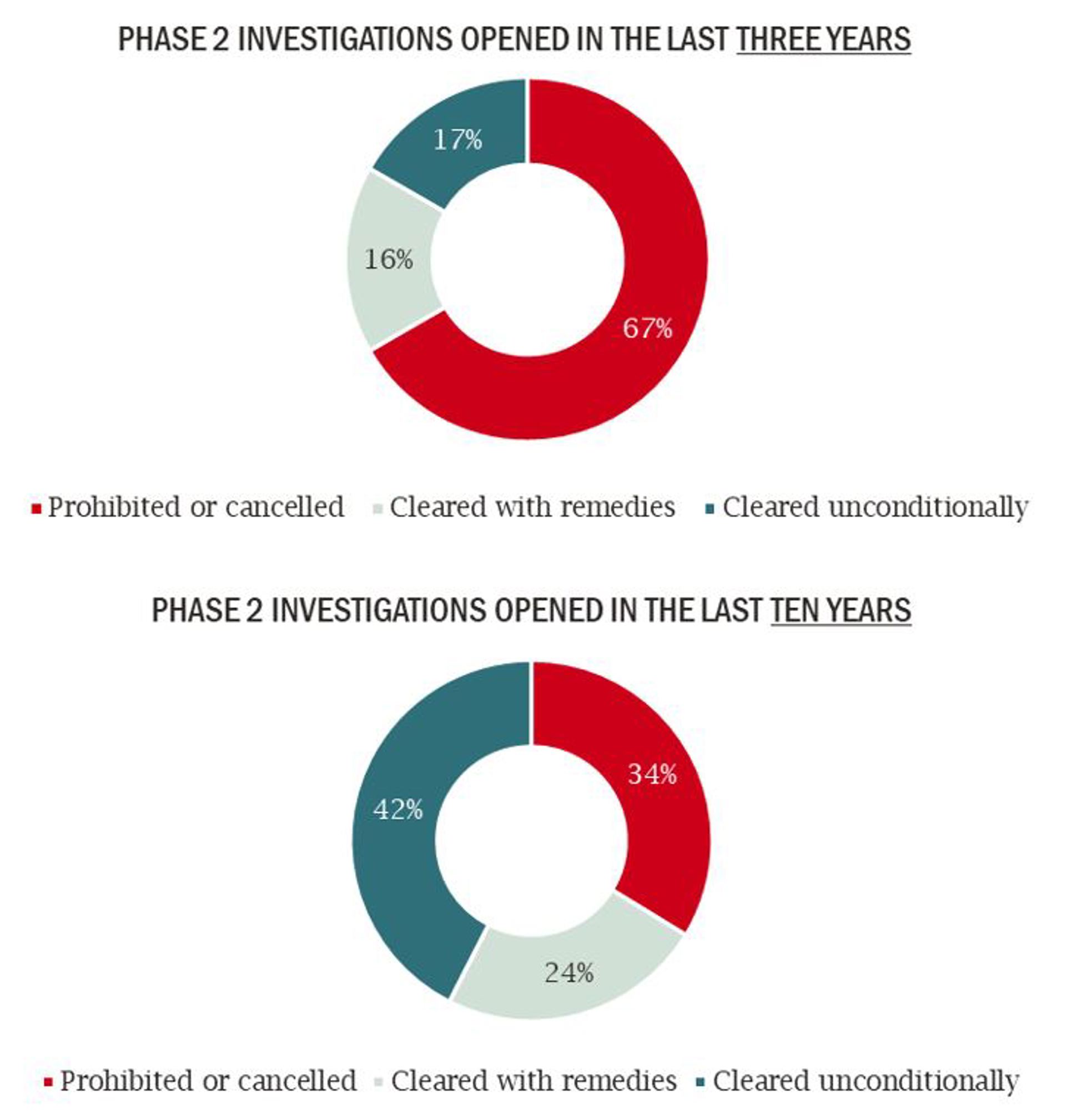

Unfortunately for many businesses, the answer will likely be yes. The CMA has developed a reputation for taking a tough line on mergers in recent years. As the second chart below shows, more than a third of in-depth (Phase 2) merger investigations opened in the UK in the last decade have resulted in outright prohibition or abandonment, with a significant share of the remainder requiring the businesses to offer remedies (such as promising to divest certain assets) to secure clearance. And the CMA appears to have become even more interventionist of late, with eight of the 12 Phase 2 investigations it opened in the last three years leading to prohibition or abandonment; only two resulted in unconditional clearance (see first chart below). This is a far lower success rate than businesses have achieved with the EC over the same period.

Figure 1 The CMA's track record on in-depth merger investigation decisions

Source: Frontier Economics

Even firms that expect to secure unconditional clearance should not bank on an easy ride, as UK businesses that have survived the meat grinder of a Phase 2 CMA investigation will be all too aware. Some smaller national competition authorities are heavily influenced by (and to some extent piggyback off) probes in the US and EU when it comes to granting clearance. Companies should not expect the CMA to take a similar approach. European firms that will be encountering the CMA for the first time would do well to study its voluminous final reports on previous merger investigations and steel themselves for some tough questioning.

The challenges confronting businesses seeking merger clearance in 2021 could be amplified by two challenges that the CMA itself faces in adapting to its new responsibilities.

- New processes. The CMA has less experience than the EC when it comes to working alongside competition authorities in other jurisdictions. Over the years, regulators in Brussels have honed a number of procedures to streamline interaction with other authorities and reduce duplication of effort (such as confidentiality waivers that, with the consent of the businesses, allow competition authorities to share information). The CMA has less experience of this regulatory ballet dance, particularly at more advanced stages of merger investigations once the question of who has jurisdiction has been resolved. While the CMA and EC will no doubt find effective ways of working alongside one another over the coming years, these processes will take time to smooth out. Businesses going up before both the EC and CMA in 2021 will be guinea pigs. They should make allowances for some inevitable inefficiency.

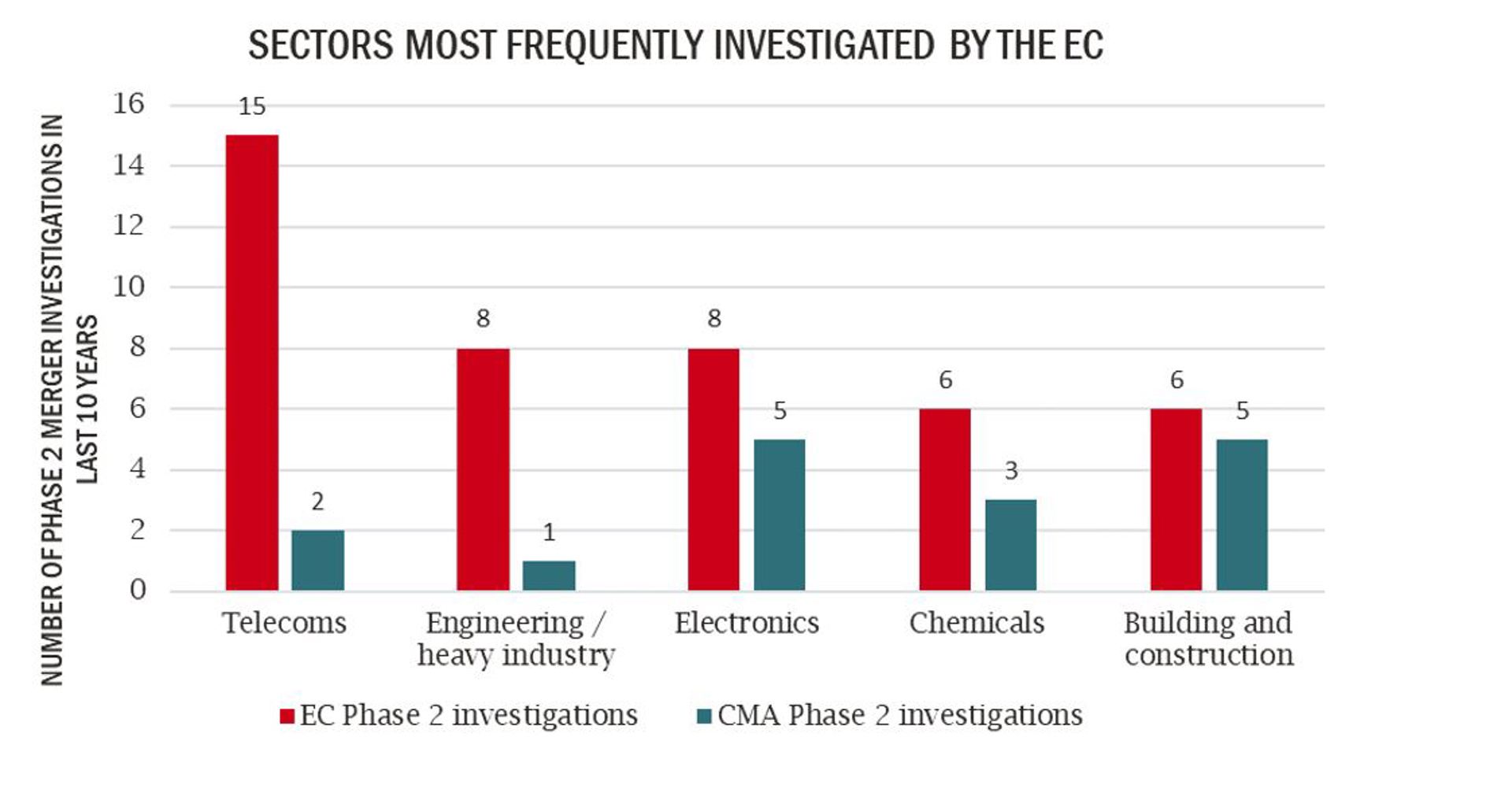

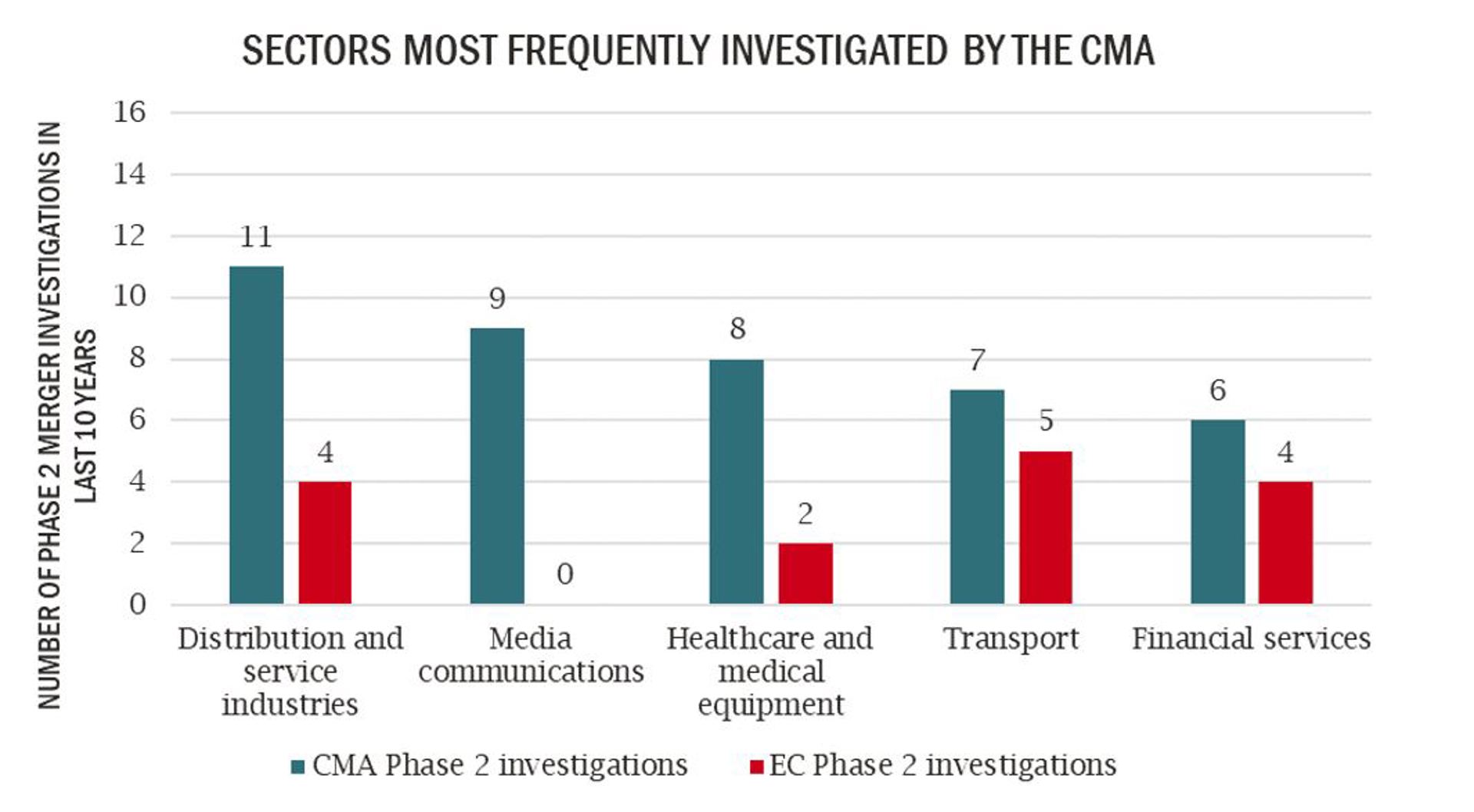

- New sectors. While the CMA has conducted investigations in a range of industries, its experience is not uniformly spread. As can be seen from the charts below, the sectors in which the CMA has most experience in merger control differ markedly from those that form the bread and butter of much of the EC’s work. European businesses that have previously locked horns with the EC should not assume that the CMA will be starting with the same baseline of knowledge about how their industry operates. For example, while the EC has conducted no fewer than fifteen Phase 2 merger investigations in the telecoms sector in the last decade, the CMA has conducted just two. In one sense, this presents an opportunity: businesses may have more scope to help shape the CMA’s thinking about a sector in which it has little previous experience. But it also means more risk: after all, for businesses that need to secure merger clearance in both Brussels and London, it can only be bad news if the EC and CMA reach different conclusions.

Figure 2 Breakdown of CMA and EC In-depth merger investigations by industry sector (top five sectors, 2010-20)

Source: Frontier Economics

With time, the CMA will no doubt master these challenges as new processes for interacting with Brussels bed in and it builds experience in unfamiliar sectors. But as the risk of short-term disruption recedes, the risk of longer-term divergence may grow. As the fraught negotiations over the level playing field between UK and EU businesses post-Brexit made clear, the UK is keen to forge its own ‘independent’ path in competition policy, which may lead London and Brussels to drift apart after decades of close alignment.

The speed and direction of this divergence is uncertain: as we explored in a recent article, the future path of UK competition policy remains especially unclear. However, the scope for divergence is amplified by the fact that competition policy as a whole is at a crossroads. A number of forces ranging from globalisation to decarbonisation are pushing policymakers to ask fundamental questions about what the overarching objectives of antitrust enforcement should be and how competition authorities should be trying to achieve them. The challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy provide perhaps the most pertinent case in point…

Click here to read about the revolution in digital antitrust, the impact of the General Court's judgment in CK Telecoms and Trucks litigation.