The European Commission (EC) and Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) are both grappling with the difficult question of how (and when) to regulate fast-moving digital markets.

The EC has published draft legislation for a Digital Markets Act (DMA), which contains a set of criteria for identifying “gatekeeper” firms that will be automatically subject to a long list of obligations. The EC is also proposing a Digital Services Act (DSA), which applies a set of rules for online intermediaries that mainly relate to accountability and transparency rather than competition issues. Meanwhile, the CMA has provided advice to the UK government on a regime for regulating digital platforms that would consist of a code of conduct, Pro-Competitive Interventions (PCIs) and greater scrutiny of mergers for firms with Strategic Market Status (SMS). This is explored in more detail in Frontier’s recent article, ‘Digital Brexit’.

The risks associated with regulatory cliff-edges

Regulators generally try to avoid regulatory cliff-edges. In particular, they try to avoid applying very different regulation to firms that have relatively similar market positions e.g. there should be limited difference in the regulation faced by a firm with a 49% market share relative to a firm with a 51% market share. Likewise, regulators also try to ensure that firms do not face large jumps in the level of regulation that they are subject to as they grow.

Regulatory cliff-edges have the potential to distort competition. Firms that are subject to regulation may have a reduced ability to compete (e.g. due to a reduced scope for differentiation), whereas firms that rely on regulation may benefit from an increased ability to compete (e.g. due to access obligations). In some ways, that is the point of regulation focussed on addressing competition issues. But it is important that regulation does not tilt the competitive dynamics too much in favour of the challenger firms, as that could also lead to an uneven playing field. Large jumps in regulation could also reduce firms’ incentives to capture market share from rivals and to innovate. If there are large discontinuities in the regulation faced by firms, then the profit-maximising strategy for some firms could be to stay just below the threshold for regulation. If the threshold for intervention is set based on the number of users, then this could provide firms with an incentive to focus more heavily on high value subscribers to the detriment of lower value subscribers.

The likelihood of regulatory cliff-edges under the EC’s and CMA’s proposals

The likelihood of regulatory cliff-edges will depend on how intrusive the potential remedies are, how much flexibility regulators have when imposing remedies and whether this flexibility is used in a proportionate manner. For example, the greatest risk of regulatory cliff-edges is likely to occur when an intrusive set of remedies are applied as soon as firms reach a certain threshold with no remedies applying below the threshold.

The EC wants to adopt more of a rules-based approach for designating firms as gatekeepers (using quantitative threshold linked to the number of users and revenues / market capitalisation) and in turn imposing obligations on such gatekeepers (with there being no scope for efficiency defences). This could suggest that there is a risk of regulatory cliff-edges under the EC’s approach, although there are a number of caveats:

- Firms will have the opportunity to provide qualitative evidence to the EC to argue that they are not gatekeepers despite meeting the quantitative thresholds (similarly the EC can rely on qualitative evidence to demonstrate that firms are gatekeepers despite not meeting the quantitative thresholds);

- As well as imposing a long list obligations on gatekeepers, the EC also wants to impose of sub-set of these obligations on prospective gatekeepers;

- The article 6 obligations are subject to further specification; and

- It would appear that some of the EC’s obligations are only applicable to certain services e.g. access to search data.

The CMA has proposed that it should have considerable flexibility under its regulatory regime, both in terms of deciding which firms have SMS and which regulations should apply. If used appropriately, this should provide the CMA with an opportunity to avoid regulatory cliff-edges. As the CMA has itself acknowledged, it is crucial that it adopts a proportionate approach. This is especially the case given that the remedies in its toolkit are largely untested and potentially intrusive. A well-established principle in other sectors, including the telecoms sector, is that regulators need to impose remedies that are proportionate to the issues identified. There also needs to be a mechanism for preventing regulatory over-reach. In telecoms, a merits-based appeals process plays this role. This not only provides a back-up option for firms when regulators attempt to impose unjustified regulation, but also results in a disciplining mechanism for regulators to get their regulation right in the first place.

The CMA will also need to consider whether any regulation should apply to all firms rather than just SMS firms. For example, in the telecoms sector, roaming regulation, mobile number portability and interoperability requirements apply to all firms and not just firms with Significant Market Power. Clearly, for regulation that applies to all firms, there is no risk of regulatory cliff-edges.

Despite the CMA’s approach generally being flexible, it has set quantitative thresholds (based on group-level revenues) for deciding which digital firms it should investigate. This could create a possibility that regulatory cliff-edges could arise because more specialised firms escape regulation, especially if they haven’t started to monetise their services yet, which is quite common in digital markets. The CMA also appears to want to investigate whether firms have SMS sequentially e.g. Google and Facebook may be investigated before any other firms. Therefore, this could result in regulation being applied sequentially, even where firms compete in the same markets – clearly this could result in an uneven playing field.

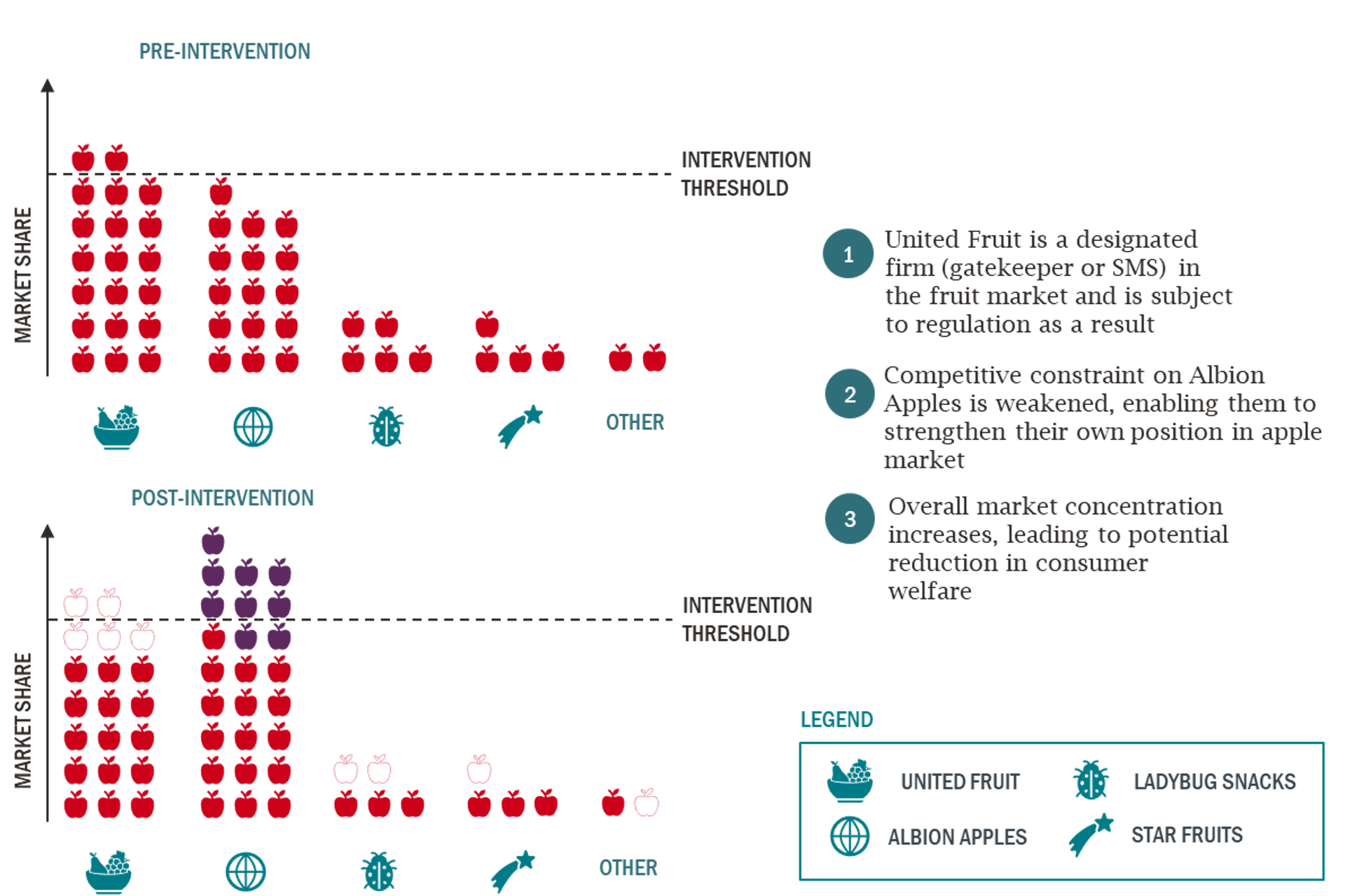

A simple example of fruit sellers vs apple sellers

Let’s step away from the highly complex digital world for a moment and think about a simpler example of apple sellers. Imagine there are a large number of apple sellers in the market, with the two largest being United Fruit and Albion Apples. United Fruit is a major supplier across all types of fruit, and is determined to be a designated firm (a firm with SMS or gatekeeper status). Meanwhile, Albion Apples falls short of being determined to be a designated firm, although it is a significant player in the market for apples. This could be due to the activity being defined as fruit selling as opposed to apple selling, or Albion Apples falling short of the group revenue threshold needed to be considered. If regulation is imposed on United Fruit, limiting its market power in the apple market, Albion Apples can take advantage of this and dramatically increase its own market share. As United Fruit and Albion Apples were each other’s main competitive constraints, lessening the constraint on Albion Apples could actually lead to an overall increase in the concentration of market power (at least in the short run, until Albion Apples is regulated in turn).

In the example above, everything has gone wrong. A regulatory cliff-edge has led to Albion Apples being overlooked by regulators, and overly intrusive remedies that only apply to firms above a certain threshold have enabled Albion Apples to capture significant market share at the expense of every other market participant. The regulator will now have to assess Albion Apple’s market power as the new designated firm, with the result being that they are evaluating market participants sequentially. The regulator will also need to consider removing regulation imposed on United Fruit, as failing to do so could result in competition worsening even further. Indeed, if the authority overshoots with its regulation, then this could result in a game of regulatory “whack a mole”.

Trade-offs

Although a more flexible approach has potential upsides, it may come at the expense of speed and legal certainty. Indeed, the EC decided to sacrifice some flexibility under its proposed approach in order to ensure that it could intervene quickly in digital markets. Given these potential sacrifices, this amplifies the need to ensure that where a more flexible approach is adopted, authorities make sure that they make the most of such flexibility by avoiding regulatory cliff-edges.