Changes to nature of work will make it tougher to head off pension poverty.

The UK government recently touched off a political storm by raising taxes to pay for long-neglected reform of social care. Without equally drastic action, a future government will be forced to take action to forestall a similar crisis - over pensions.

Britons save far too little for their old age, a problem that current trends are magnifying. For instance, stagnant wages make it harder to save for the future; rising longevity means we need to work longer to afford retirement.

The upshot is that the UK will be scarred by widespread pensioner poverty unless it takes bold steps to make people save more. Concretely, the minimum auto enrolment contribution to an employee's pension savings needs to rise from 8% of qualifying earnings now to something in the order of 15% to secure a decent standard of living in retirement.

The savings gap

Automatic enrolment, launched in 2012, has been a great success – up to a point.

For decades, pension providers and the government had failed to persuade people to put aside more money to supplement their state pension, which is one of the least generous in Europe.

With automatic enrolment, the pension participation rate among employees jumped from about 50% to 75%. Employers must pay 3% of the minimum contribution rate and employees the remaining 5% - unless they take the conscious decision to opt out.

Policymakers had assumed that, once people had been nudged into salting away a chunk of their salary for their old age, they would take more of an interest in their pension and would see the need to top up their contribution. The problem is that they haven’t.

What is clear is that the current default enrolment rate is inadequate. Current rates might just about generate a retirement pot of £150,000 for someone who works continuously for nearly 50 years and earns an average wage over that time. That sounds like a lot of money, but it goes quickly when spread over 20 or more years of retirement.

And a glance at the government’s social care reforms shows a lifetime care cap of £86,000 – a rather daunting prospect. Doubling savings rates could have the pension pot grow to £300,000. Care costs immediately look more manageable.

Equally, a higher savings rate would make more room for the messy reality of life - career breaks, part-time working or the inability to work beyond a certain age.

Trends in work pile on the pressure

The current pension system is operating on razor-thin margins, which means that wider trends in work can easily put a decent retirement in jeopardy.

The key trend is the stalling of real wage growth, reflecting a deeper trend particular to the UK of poor productivity. Because retirement income is determined by the accumulation of savings made over a working lifetime of 40 years or more, the stagnation of wage growth is of paramount importance.

The potential for automation and AI remains to be seen. It could boost productivity and wages. It could also lead to widespread job losses. Economies have always adjusted in the past, but the transition can be painful and may leave cohorts of workers with patchy careers, even lower savings and strained retirements.

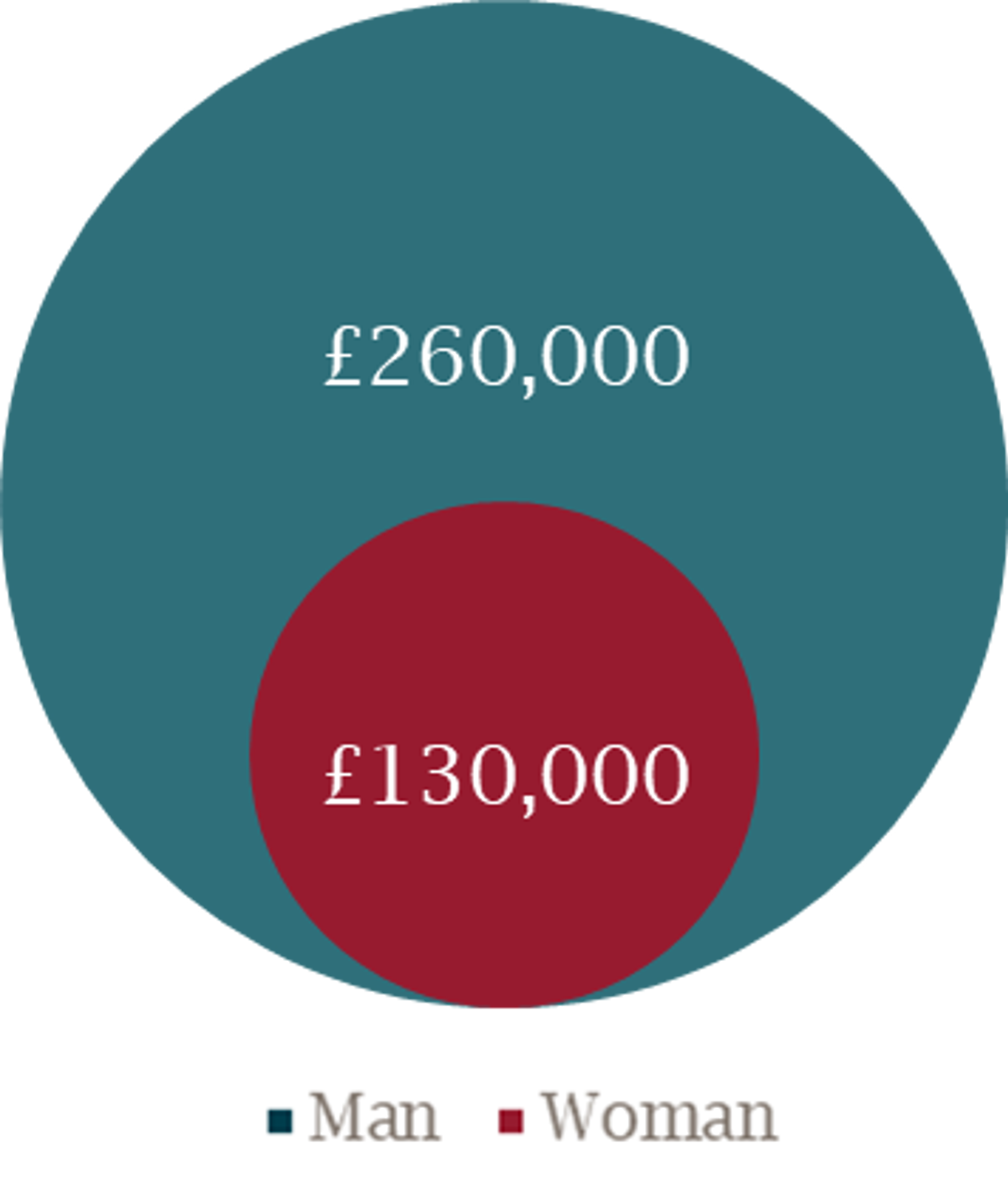

There also remain sizable gender inequalities in the workforce. The average pension pot today for a man aged 65-74 is £260,000, compared to £130,000 for a woman. Such a gap is unlikely to be closed given continuing trends in the workforce. In particular, women remain much more likely to work part time (75% of part-timers are women) and take career breaks. That lowers women’s lifetime earnings and associated pension savings, leaving them at risk of a poor retirement.

Figure 1: The average pension pot today for a man and a woman aged 65-74

A sharp dig in the ribs

Greater government support is one solution. A common refrain is that it is unfair to the young to keep increasing the state pension. But in fact they may be the greatest beneficiaries, as sustained increases would give them a decent pension by the time they retire, thanks to compound growth.

More challenging is demography. The ratio of pensioners to the working-age population is projected to rise to 367 per 1,000 by 2042 from 300 today, an increase of 20%. That means a substantial increase in state pensions would need massive tax rises, something that looks politically difficult to say the least.

So, much of the solution to the savings gap lies with individuals. For most workers today what they put into their pension during their working life determines – along with their employer’s contribution – what they take out in retirement, plus or minus investment returns.

The critical point to grasp is that retirement outcomes are the product of savings habits ingrained over an entire working life. The sooner policymakers act, the better off people will be in their old age. The biggest policy risk is to do nothing.

Some changes are in train. The Money and Pensions Service is developing pensions dashboards to make it easier for people to see all their retirement pots in one place, and this may help to improve engagement.

But such initiatives, while worthy, probably won’t tackle the underlying problem. The average employee must save a lot more to maintain their quality of life into retirement. To that end, policymakers need to give them more than a new nudge. Only a sharp dig in the ribs will do.