Brussels expanding energy priorities

June’s elections to the European Parliament may not capture global attention to the same degree as November’s vote for a new US president.

But the elections, accompanied later in 2024 by the start of a five-year term for a new European Commission, remain consequential. This holds especially true for energy and climate policy, an area in which Brussels is increasingly influential. In this article, we take a look at some themes that will feature on the EU policymaking agenda over the coming years.

1.Taking stock: Adjusting priorities at time of crisis

To get a firm idea of the direction of travel, it is worth looking back at EU energy and climate policymaking over the last five years. Since 2019, the EU has adopted a raft of measures to support decarbonisation of the economy, including:

- new and/or tighter targets for greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy and efficiency (including the introduction of a landmark climate neutrality goal for 2050);

- reforms to existing greenhouse emissions trading for power and large industry, its extension to the EU maritime sector, and the introduction of a separate emissions trading scheme for buildings and road transport; and

- rules governing the organisation of new markets for hydrogen and decarbonised gases.

However, while the current Commission’s initial focus was on tackling climate change, it has also had to respond to crises and political pressure over its term. As it has done so, it has introduced new frameworks to deal with perceived threats, including:

- emergency rules to address high and volatile energy prices;

- reforms to electricity markets to promote investment in non-fossil-fuel technologies and to facilitate longer-term contracting (to help price stability); and

- measures to support EU industrial and critical raw materials processing capacity.

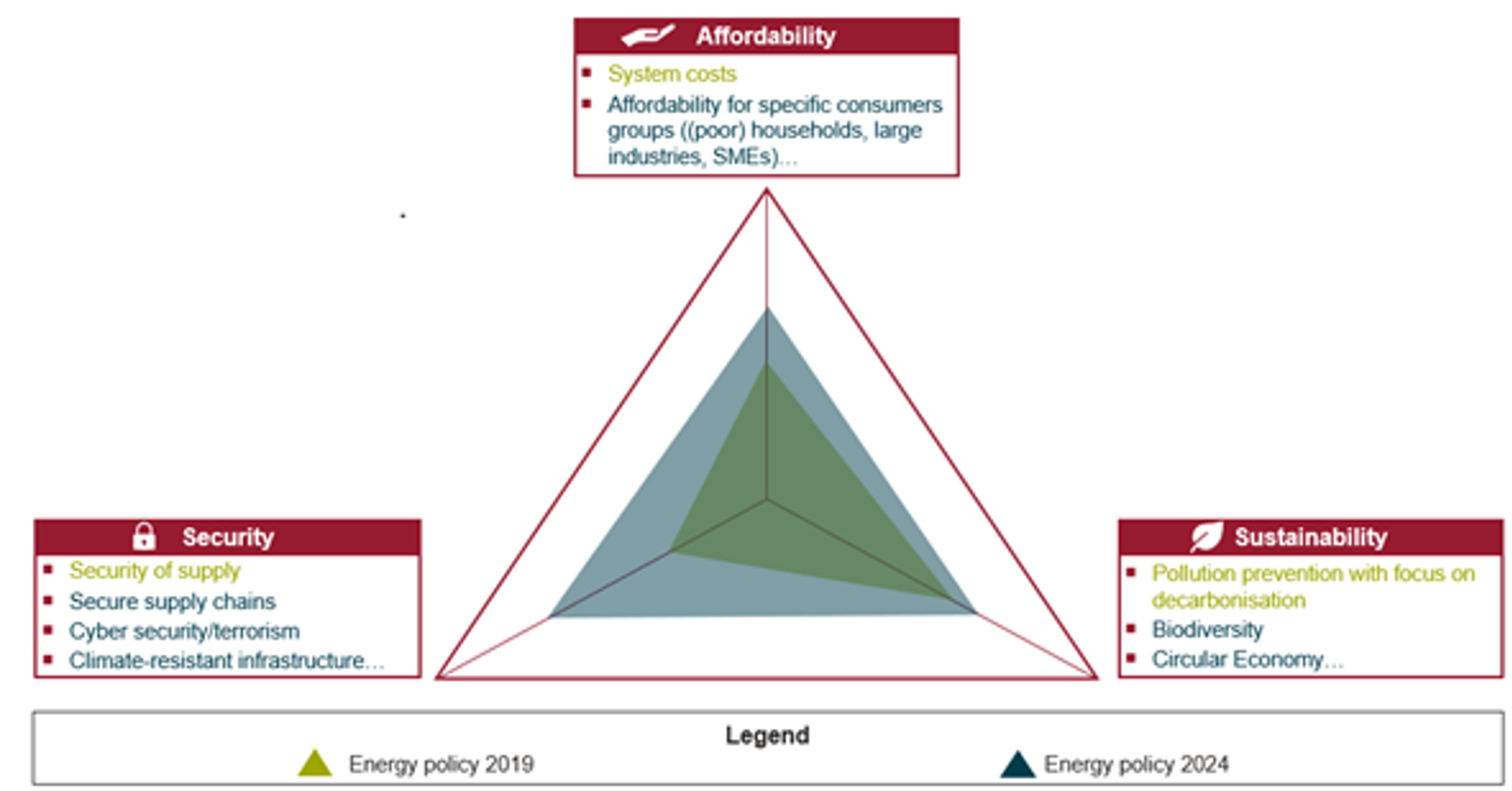

The measures that have been introduced have accompanied an evolution in the traditional energy policymaking trilemma of objectives (energy security, sustainability and affordability).

These three goals are interlinked. Sometimes, they reinforce each other (e.g. in the case of energy efficiency). In other cases (e.g. in relation to support for the deployment of maturing low-carbon technologies) there are tensions between them, at least in the short term.

Figure 1 - The shifting focus (and widening scope) of the EC’s energy trilemma – illustrative diagram

Source: Frontier Economics

Clearly, over the current Commission’s five years in office the emphasis on energy security within the trilemma has increased, given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the policy discourse has revealed that policymakers are having to make increasingly complex trade-offs when it comes to energy policy. For example:

- Sustainability has many dimensions: Enhancing the EU’s “strategic autonomy”, such as its ability to mine and process critical raw materials, may reduce the risks attached to meeting EU decarbonisation goals but may come with increased costs – both in terms of the public purse and the impacts on the wider environment.

- Solidarity increasingly matters: There may not always be a convenient match between the countries where action is needed to cost-effectively meet EU climate and energy goals and the ability of member states to finance such actions.

- Investor risk versus system efficiency: Greater price stability may help reduce volatility for investors (and so bring down the costs of financial support for low-carbon technologies). But reduced exposure to price signals may raise the costs of building and running the energy system. While this trade-off is not new, it is one that has come increasingly under the spotlight given the debate on electricity market design.

2 Looking ahead: emerging themes

It would be unwise to bet on a crisis-free Commission term for 2024-29. That said, regardless of the political or economic backdrop, it is likely that, in addition to continued attention to security of supply, priorities will include:

- ensuring the EU is on track to achieve recently agreed targets for 2030; and

- planning for the delivery of 2040 targets. The Commission is expected to set out a proposal for a 2040 climate target later in Q1 2024.

Alongside these main aims, stakeholders and the Commission itself appear to be gearing up for further action. Lots of ideas are floating around, with many falling into the following buckets:

- Grid development: in response to stakeholder feedback, the Commission released an action plan for grid development at the end of 2023. While mainly non-legislative in nature, it suggests a number of areas to facilitate the financing and faster delivery of electricity networks – both on- and offshore.

- System planning: papers from think tanks including the Florence School of Regulation and Bruegel identify potential reforms to address perceived inefficiencies in the current institutional set-up. Suggestions include greater co-ordination of energy planning between EU member states, the creation of an independent pan-EU energy network operator with responsibility for system planning and/or the merging of existing network operator associations.

- Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS): the Commission is currently preparing a strategy for CCUS. As with the grid action plan, steps in the near term are likely to be non-legislative, but the Commission may set out a blueprint for legislative action to be picked up by its successor.

- EU Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading System(s) (EU ETS): During the current cycle, the EU tightened the ETS scheme for power and heavy industry (ETS-1) and created a parallel “ETS-2” scheme covering buildings and transport emissions, to align with more ambitious climate targets. The next Commission may need to propose some adjustments to the schemes.

-

-

- For example, two challenges that may arise as the ETS-1 cap gradually tightens towards zero (expected before 2040) are liquidity constraints (making it harder for operators to secure emissions allowances, affecting price volatility), and the treatment of negative emissions, such as those from systems like CCUS (raising the question of whether these will be considered as carbon allowances).

- Moreover, the next Commission may need to intervene in the design of ETS-2, which is set to enter into force in 2027/2028. Depending on the success of the scheme, the EU may want to revisit factors such as the allowance amount, the release of additional allowances in response to high prices, and explore options to enhance the convergence between the ETS systems’ prices.

-

3 How economics can help untangle the challenges

The current cycle of EU policymaking has raised plenty of interesting economic issues, and the next one is unlikely to be any different. Taking just the themes outlined above, some important economic considerations arise:

- While it is clear that huge investments are required in energy networks in coming years, regulators nevertheless face uncertainty as to the mix and location of investment. Given this uncertainty, how can they effectively balance the need to support the green transition while protecting energy consumers?

- How best to capture the various energy system interactions (between countries and regions, between local energy distribution and long-distance transmission, between energy carriers) when looking at energy system planning?

- How best to deal with the multiple risks and barriers facing investors across the CCUS value chain (emitters, capture, transport, storage, etc.)? How to deal with higher costs for early investments?

- How can we best design a GHG emissions pricing system that is sufficiently credible and effective in supporting decarbonisation, while at the same time protecting (vulnerable) consumers? Is there a pathway towards greater convergence of parallel emissions trading schemes in the long run?

There are no simple answers to these questions. Rather, while economics might provide a framework to help think about such issues (e.g. what value to put on different policy options in the face of uncertainty), the appropriate response will likely be specific to the geographic and political context. We look forward to engaging in the debate with our clients and with stakeholders.